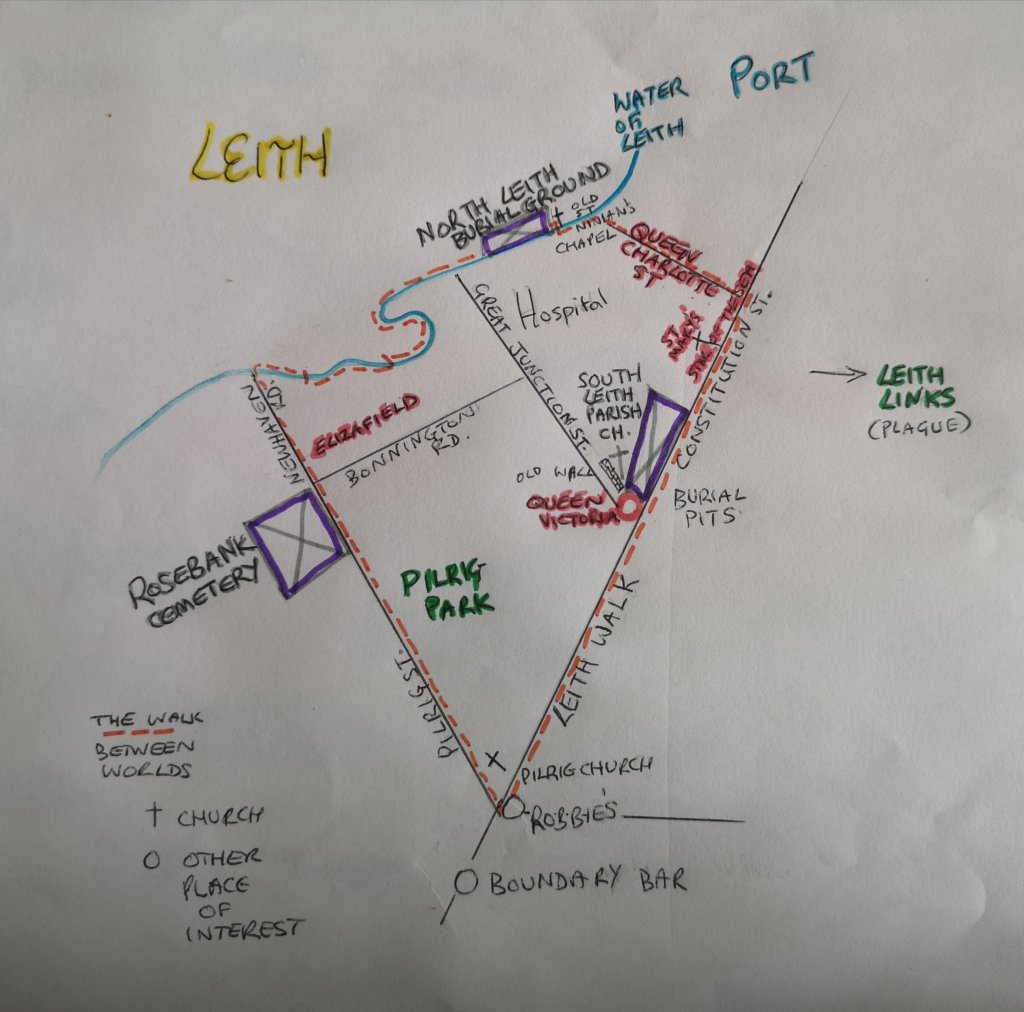

An account of the second part of a circular tour of Leith beginning at Bonnington Toll.

Focus on women

I chose to focus on women’s stories during this walk, because, as a woman and a feminist, it is necessary to know about who came before me, I need to know my backstory. I find that it helps me sense my place in the continuum of the generations. Several of these walks took place at the same time as the Audacious Women Festival, whose byline is: ‘Do What You Always Wish You Dared’. I was involved in the 2019 Audacious Women Festival, sitting on a panel which looked at women who travel and move to different countries: how we support ourselves, make friends, manage the language difficulties and so on. That women-only event engendered a lively discussion with the audience, in which women of all ages shared their emigrant and immigrant experiences. My first guided walks was open to men and women, children and dogs, and it was something I was daring myself to do!

Bonnington

After leaving the Rosebank Cemetery, we cross Bonnington Road, a toll road at the end of the 18th century. We enter into what would have been Bonnytoun (pretty village in Scots), encompassing mills and land which was part of the Barony of Broughton (mentioned in a Royal Charter 1143). Flanking both sides of the road are modern estates as well as the much older red stone Burns Tenements (on the right), which used to be the tannery. We were also going to be seeing the graves of leather workers with their pincer tongs and other tools adorning them in the North Leith Burial Ground, further along the way. Using the power of the Water of Leith, there was a conglomeration of businesses in the Bonnytoun area, and there is one existing mill wheel in the mill lade at Bonnyhaugh Cottages (on the left).

Second on the right is Elizafield, named after Eliza, a native of Leith, and the woman who bore Dr. Robert Grant. I have not been able to find out anything about her and her life. Her story has disappeared, perhaps deemed less important than his despite the fact that he would not exist if it weren’t for her, not least because birthing was such a dangerous task in the 1780’s. Grant was a surgeon and left Leith in his twenties to settle, very successfully, in South Carolina (US) marrying Sarah Foxworth. The rice plantation he established in Georgia (US) was also named Elizafield, and, as was the way then, it only drew the produce and profits it did, due to the female and male slaves who carried out the work: they were, ‘the driving force behind the success of the plantation’. (Amy Hedrick, author on glynngen.com)

Historically it [birth] was thoroughly natural, wholly unmedical, and gravely dangerous. Only from the early eighteenth century did doctors begin getting seriously involved, with obstetrics becoming a medically respectable specialty and a rash of new hospitals being built. Unfortunately, the impact of both was bad. Puerperal, or childbed, fever was a mystery, but both doctors and hospitals made it worse. Wherever the medical men went the disease grew more common, and in their hospitals it was commonest of all.

Druin Burch (2009) https://www.livescience.com/3210-childbirth-natural-deadly.html

We turn our backs on Elizafield to view Flaxmill Place. Flax was used to make linen, most of which was exported. It was so successful (employing 10000-12000 workers, many of whom would have been women, although the data is unavailable), that we know the Mills were able to loan Edinburgh Council a great deal of money. The Bonnington Mills, on the banks of the Water of Leith, made woollen cloth as well as linen and much of the wool was produced by women in their own homes nearby. The owners were always aiming to improve profits and cut corners, which resulted in the controversial introduction of Flemish and French workers (accommodated at Little Picardy(ie), the current Picardy Place). The women and girls spun the cambric yarn (for the close-woven, light type of linen), to try and improve the quality of the cloth, but this took away the local jobs.

In 1686, the first Parliament of James VII passed an ‘Act for Burying in Scots Linen’, the object of which was to keep the cloth in the country. It was enacted that, “hereafter no corpse of any persons whatsoever shall be buried in any shirt, sheet, or anything else except in plain linen, or cloth of hards, made and spun within the kingdom, without lace or point.” Heavy penalties were attached to breaches of the Act, and it was made the duty of the parish minister to receive, record and produce certificates of the fact that all bodies were buried as directed. On hearing this, we can imagine that the women in the graves we were visiting may have been bound in just such a linen shroud, made right in this place.

Before the Industrial Revolution, hand spinning had been a widespread female employment. It could take as many as ten spinners to provide one hand-loom weaver with yarn, and men did not spin, so most of the workers in the textile industry were women. The new textile machines of the Industrial Revolution changed that. Wages for hand-spinning fell, and many rural women who had previously spun found themselves unemployed. In a few locations, new cottage industries such as straw-plaiting and lace-making grew and took the place of spinning, but in other locations women remained unemployed.

Joyce Burnett (2008) This webpage has some fascinating pictures of women spinning at home and in the factory

A little further up the road is the original site of the Chancellot Mill (now on Lindsay Place) and this was where corn was ground into flour (perhaps the reason for those corn cobs on the Persevere flag?) It was steam powered and had an 185 foot high clock tower. Producing 43 sacks an hour (twice the original prediction), it was described as ‘the most handsome flour mill in the world’!

Urban myth

They were growing cannabis in the basement of The Bonnington and it spontaneously combusted in the middle of the night, causing the whole building to burn down. True or false?

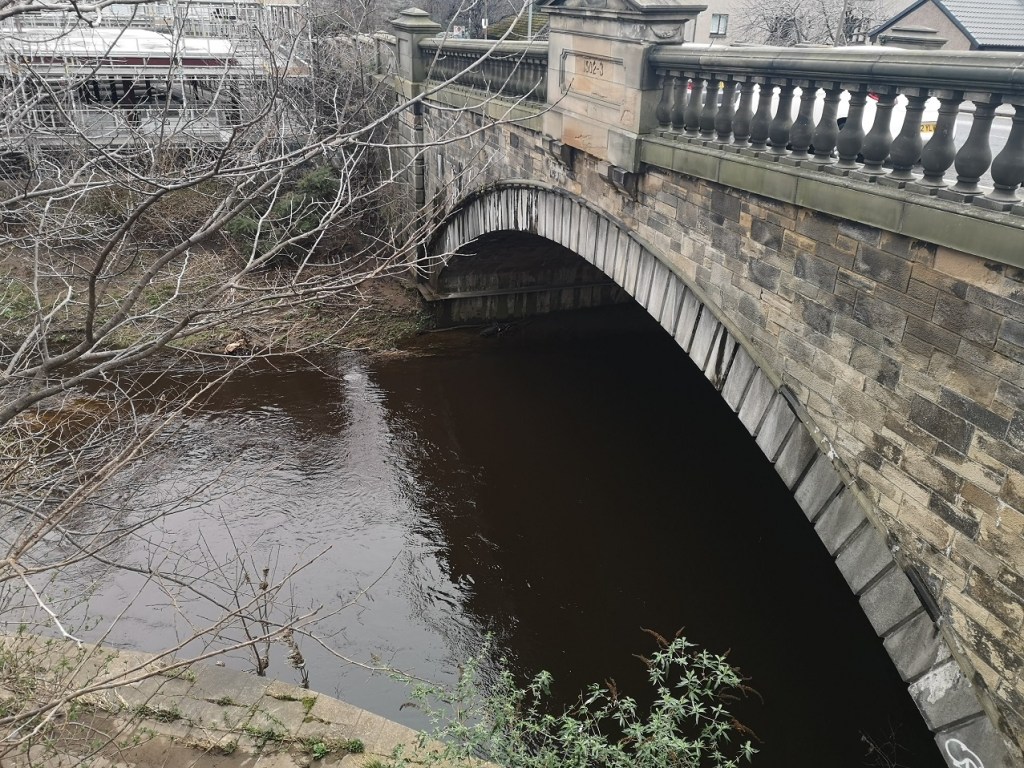

Water of Leith

I invite you to look into the water here and think of the phrase ‘time immemorial’. Legally, this refers to the years before 1189, being the date set, in 1275, as the time before which no one could remember, and therefore no legal cases could deal with events before that date. ‘Time out of mind,’ recorded from the fifteenth century, is just the plain English version of the same thing. My information came from here and here.

As we cross Anderson Place, this quote from the Tao Te Ching is one to ponder: “The Master gives herself up to whatever the moment brings. She knows that she is going to die, and she has nothing left to hold on to: no illusions in her mind, no resistances in her body. She doesn’t think about her actions; they flow from the core of her being. She holds nothing back from life; therefore she is ready for death, as a woman is ready for sleep after a good day’s work.” (50)

North Leith Burial Ground

After rounding the corner of the Water of Leith and meeting the confluence of the wonderful network of Edinburgh cycle paths, we mount the steps onto Coburg Street where the North Leith Burial Ground is situated. According to The Spirit of Leithers (a Facebook Group) it is ‘The dead centre of Leith’!

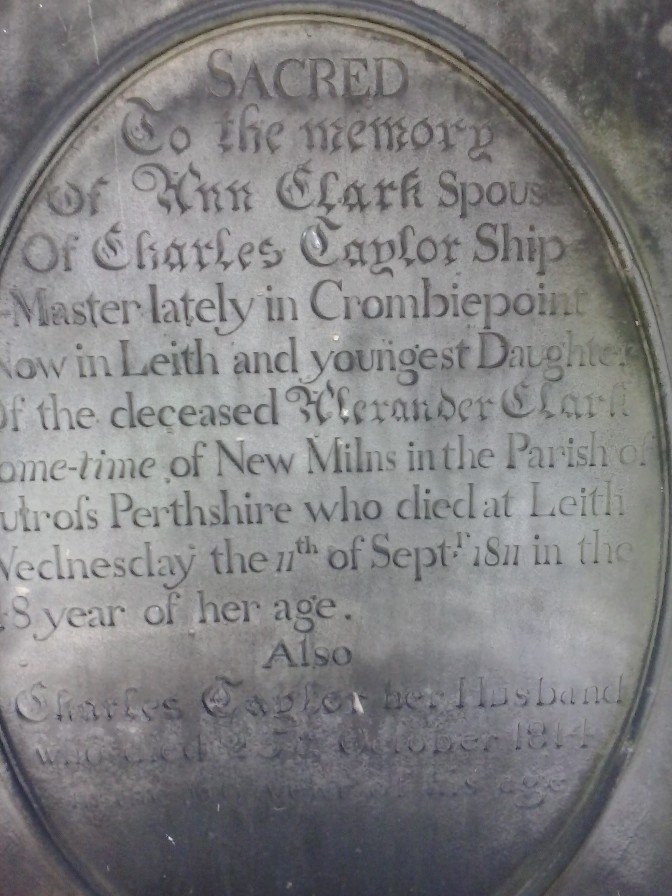

The memorial stones are old (1664 – 1820) and varied. There are grand mausoleums, individual slabs – some half buried and unintelligible – and almost all have engravings worth seeing. This is a good time for a ‘treasure hunt’: search for the grave of Lady Mackintosh; a long bone; angels; and hourglasses (note: some are on their sides and others upstanding, the sands of time sifting down through the narrow neck as life passes by).

Lady Mackintosh is famous for raising a regiment for Prince Charlie’s 1745 uprising (variously known as the Jacobite, the ’45 rebellion or the ’45). It was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart.

In fact Lady Mackintosh is not here – she probably lies under the flats next door! How many people know that they are working or living over the top of dead bodies?

This was originally a series of guided walks, in-person ones (eg in celebration of the Terminalia Psychogeography Festival (23rd Feb, annually which happily coincided with the Women Who Walk Network and Audacious Women Festival (AWF)), and online during Covid. I would like to thank everyone who came along with me.

Previous: Introduction to walking Between Worlds and Walking Between Worlds 1

The walk continues in the final blog of the series, Walking Between Worlds – 3

If you have information about the women who are featured in the walk, have made a similar walk, or would like to share anything about these subjects, please do so in the comments box below.