The third and final part of a circular tour of Leith, starting at the North Leith Burial Ground.

Along the road and down to the right beside Coburg House artists studios (well worth a visit) is the gloriously orange, former St Ninian’s Chapel (you can see St Ninian himself (360 – 432 AD) carved onto the doors and representing the Picts, at St Andrew’s House (St Andrew’s Square) in the centre of Edinburgh.) St Ninian’s Chapel is a 15th century bridge chapel, part of the complicated history of North Leith Parish Church which can be found on Wikipedia.

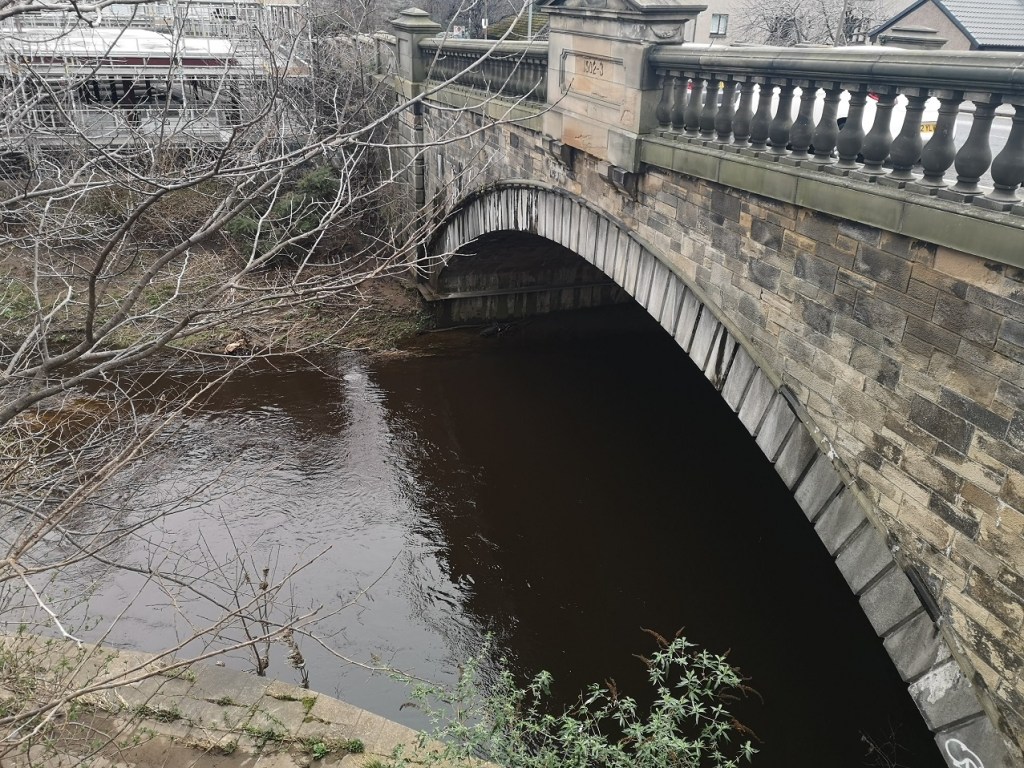

As we crossed Sandport Bridge, I drew attention to Broad Wynd on the left, where the Leith Dispensary and Humane Society hospital and clinic were first situated (of which, more later).

Along Tolbooth Wynd we wandered, and on to Queen Charlotte Street, named after the Queen of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (1744-1818). She is remembered in Queens Square, Bloomsbury, London with a statue (see above). The Leith stories were starting to fit into themes: Charlotte was an immigrant and did not support slavery. Also a botanist, she founded Kew Gardens, was married to King George III, had fifteen (that’s 15!) children and was, famously, painted by Allan Ramsey 1762 when she was aged 17 years. She was an anti-slavery campaigner and that portrait is owned by the Scottish National Galleries. Recent articles have posed the question, ‘Is she of African origin?’

At the Hideout Cafe (where I had a delicious and expensive hot chocolate on a previous occasion), we turned onto Constitution Street which was shut to traffic on account of the endless and frustrating tram works when I walked with the groups (so blessedly quiet to walk along) but is now open in all its splendour. Listen out for the dining of those tram bells announcing their arrival! We continued on, past St Mary’s Star of the Sea Catholic church, to the South Leith Parish Church and its graveyard.

St Mary’s Star of the Sea is the home of the missionary oblates

Hail, Queen of Heav'n, the ocean Star,

Guide of the wand'rer here below!

Thrown on life's surge we claim thy care,

Save us from peril and from woe.

Mother of Christ, Star of the sea,

Pray for the wanderer, pray for me

Based on the anonymous Latin hymn, Ave Maris Stella

I spent some time researching the women in this kirkyard, trying to find out their stories, but to almost no avail. I focused on another Charlotte, Charlotte Lindesay (1780-1857, who died aged 77) and discovered that she was one of a brood of six from Feddinch in Fife, and that her parents were William Lindesay and Elizabeth Balfour. In 1805, she married her cousin, Patrick who was very active in the community. Amongst other things, he was the president of the Leith Dispensary and Humane Society (see above) which was formed in 1825 on Maritime Street, later to become Leith Hospital on Mill Lane, and brought healthcare (via a clinic and hospital both initially in Broad Wynd) to the poor. I like to imagine Charlotte accompanying him, or even visiting the needy with a basket over her arm as portrayed in countless Jane Austen films, but I am woefully ill informed about her particulars.

Some of my information was gleaned from ‘The Jacobite Grenadier’ by Gavin Wood.

Incidentally, the Leith King James Hospital was demolished in 1822, and part of the wall can still be seen today, forming the boundary between the Kirkgate and the South Leith Kirkyard.

Some other women associated with this church

Mary of Guise (also called Mary of Lorraine), ruled Scotland as regent from 1554 until her death in 1560. A noblewoman from the Lotharingian House of Guise, which played a prominent role in 16th-century French politics, Mary became queen consort upon her marriage to King James V of Scotland in 1538. (Wikipedia). She worshipped at this church in 1559 and her coat of arms is displayed in the entrance today. Mary had fortified the town and she was in Leith being guarded by the thousands of French troops stationed there at the time.

There is also an altar dedicated to St Barbara who, we are told, had a very sad and sorry life. She wanted to dedicate herself to Christ, instead of marrying the man her father wanted her to (Dioscorus, 7th century), and so she was tortured and her head was chopped off by said dad. He got his comeuppance, apparently, being struck by lightening and reduced to ashes. She is, therefore, invoked in thunderstorms, and is also the patroness of miners although I am not sure why. (From the Britannica and Archdiocese of St Andrews on facebook).

When excavating for the trams, they found mass graves. There were 50 per cent more bodies of women than men, and everyone was smaller and showed signs of malnourishment compared to the national average. An exhibition and book were made and it was posited that their low weight had something to do with the plague and/or that they were from the workhouse.

As a way of paying respect to the women whose names I discovered here, I read out a list of them to those I was walking with, together with their relationships, but omitted the names of their male relatives. I was attempting to recognise how many there were and about whom we know so little, as well as the manner in which they were remembered.

I have used the original spelling from the graves. They are referred to by their maiden names.

- Elizabeth P. K. Smith Known as Betty by her friends

- Helen their daughter whose dust reposes in the Church-yard of Thurso in Caithness being there suddenly cut off in the flower of her age

- Elizabeth Maxwell, Maiden Lady Daughter of…who liv’d much esteem’d and Died regrated by all who had the Pleasure of her Aquaintance

- Mary Jackson his Spoufe who departed this Life…much and juftly regrated, being poffeffed of the moft amiable accomplifhments…also near this lyes three of her Children who all dyed before herfelf

- Ann McRuear Relick of…

- Barbara Adamson, Spouse of…

- In memory of his grandmother Mrs Ann Kerr… aged 76 years, His aunt Jean Tait.. aged 40 years, His mother Robina Tait… aged 44 years, His niece Jane Briggs Dickson …aged 33 months

- Here lyth Jeane Bartleman Spouse to…

- Sacred to the memory of Jessie Blacke..Beloved Wife of…Also of her infant baby…aged one month

- Juliana Walker Wife of …. Janet Scott their third daughter of…

- Catherine Stewart Rennie (wee Kitty daughter…)

- Mary Finlay or Best …. And of her Grandchild Margaret Dick who after a few days illness … aged 18 years Let the Young Reflect on the Uncertainty of Human Life…

Once in Robbies bar on the corner of Iona Street and Leith Walk, more or less opposite the start, I summed up the walk: It had taken us approximately 2.5 hours and we mused and meditated on boundaries and borders. We talked of the contrasts between one community of people and another and how often this causes stress at the join between areas (we were sitting close to the boundary between Leith and Edinburgh), about how we felt different at dusk and at dawn as we cross over from dark to light and vice versa, and whether we notice how we are on the cusp of the new moon. We spoke of women’s stories – in the past and now – and how they are so often seen through the lens of their menfolk and consequently hard to celebrate in their own right. And, finally we discussed the hardship of life in centuries gone by, especially how close death was, and about its symbols and community rites.

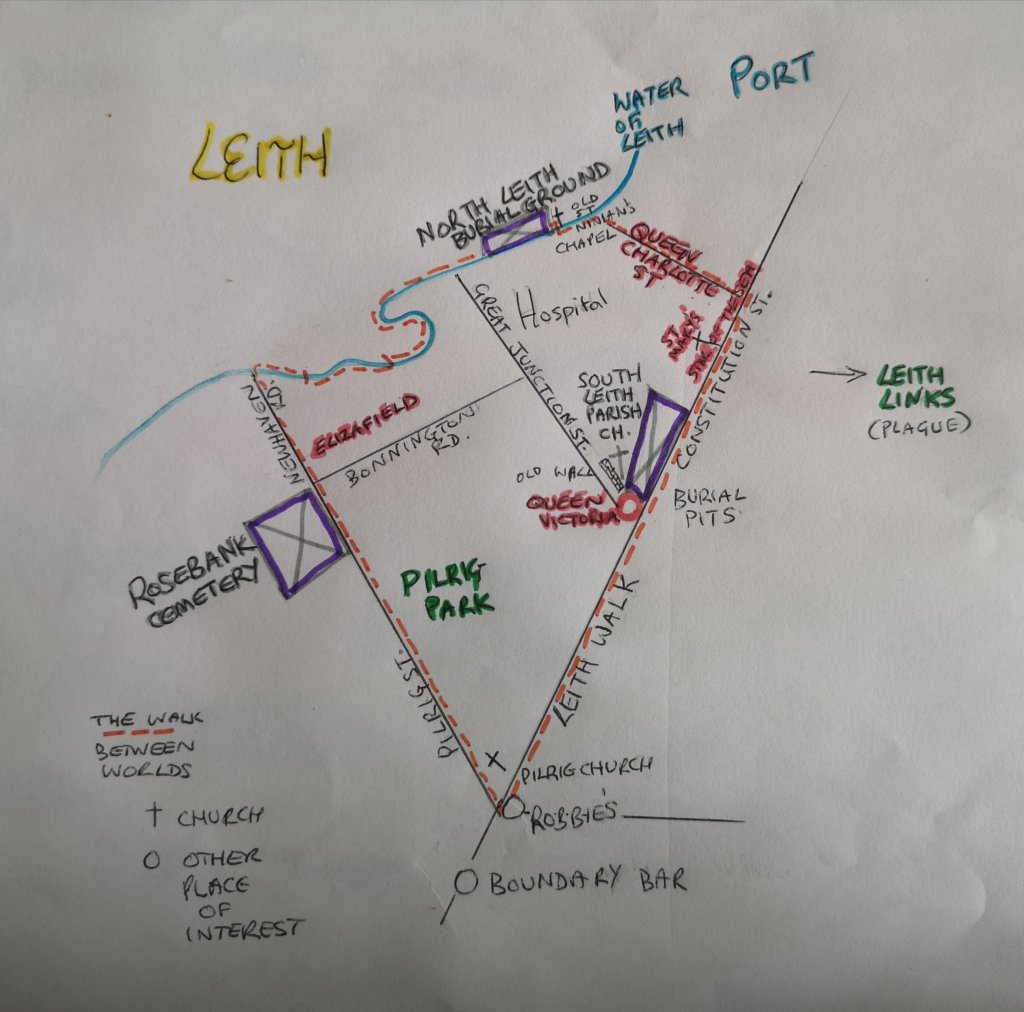

I explained that I hoped to make a map which somehow denotes and represents this event, that will contain some of its psychogeography. Wikipedia quotes Guy Debord on this: psychogeography is “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.” I think of it as a human map, not simply one containing measurements and precise locations, but including feelings, activities and conversational responses as well.

This was originally a series of guided walks, in-person ones (eg in celebration of the Terminalia Psychogeography Festival (23rd Feb, annually which happily coincided with the Women Who Walk Network and Audacious Women Festival (AWF)), and online during Covid. I would like to thank everyone who came along with me.

If you have information about the women who are featured in the walk, have made a similar walk, or would like to share anything about these subjects, please do so in the comments box below.

Walking Between Worlds – an introduction

For a lovely blog on Warriston Cemetery, see Edinburgh Drift