May 17 2020, 7.10-10.10am

This walk was inspired by a prompt from Alisa Oleva and The Resident’s Association which went like this: ‘Go out on a walk, take photos of all the things and surfaces you would like to touch, but don’t touch them.’

I tried, I really did, but I failed at the first and last hurdles (and several in between if I’m honest). Who would have thought it would be so difficult? Although, given I touch for a living it’s not so surprising. I can’t give Shiatsu because of the Covid-19 virus restrictions, so this brief is apposite.

It was my phone I touched at the off – to take photos. Smooth and cool and about the weight of a nice big juicy apple, it quickly heated up in my hand. I was on a walk I have done once before which ended on a road (link) so I wanted to find a better way back.

As soon as I started I wanted to reach out and feel the difference between the nettles and the dead nettles, even if one sort would surely sting me. It didn’t take long for my toddler instinct to kick in – ‘But I want to touch!’ I resisted.

When a wall reared up in front of me, my protesting teenager was taunted – ‘Just cos you say I shouldn’t touch, doesn’t mean I can’t!’ Though I was grown up and I didn’t.

As I passed the buttercups I could imagine the smooth, silky petals. I’m a tactile person. I have honed my sense of touch to a very sensitive degree over tens of years. The mere sight stimulated the part of my brain which remembered the feel from before (as it does with most people) – my brain’s sensory cortex.

“When asked to imagine the difference between touching a cold, slick piece of metal and the warm fur of a kitten, most people admit that they can literally ‘feel’ the two sensations in their ‘mind’s touch,’” said Kaspar Meyer, the lead author of a study into touch.

“The same happened to our subjects when we showed them video clips of hands touching varied objects,” he said. “Our results show that ‘feeling with the mind’s touch’ activates the same parts of the brain that would respond to actual touch.”

Rick Nauert on Psychcentral.com

I saw stalk ends which I was convinced would be dry and rough. The torn-off strands might feel like threads, but I couldn’t be sure. The gnarled tree, all crooked and twisted, must feel just as dessicated, I conjectured, but harder. I was pretty sure I could lean into it and it wouldn’t fall over whereas the stem would have, of course. Colder than the trunk, the Hedera helix (a better monica than ‘common ivy’ in this case) would feel the least substantial, but the shiniest. Isn’t it fascinating that we use visually descriptive words like ‘shiny’ to describe the feel of something?

While it is customary to assert that we see with our eyes, touch with our hands, and hear with our ears, we live in a simultaneous universe where sensory events and their constituent elements have a natural tendency to overlap.

Brain World

The undergrowth to my right was still opaque with dew, its wetness indistinguishable from its colour. But I didn’t touch; my eyes just feasted. (There’s another of those sensory comminglings). As I wandered on, I wondered, can you feel a colour? Would that pale grey-green feel the same as the vibrant gloss-green of that ivy I had just passed? It would be impossible to subtract the wetness from one in order to compare I reckoned.

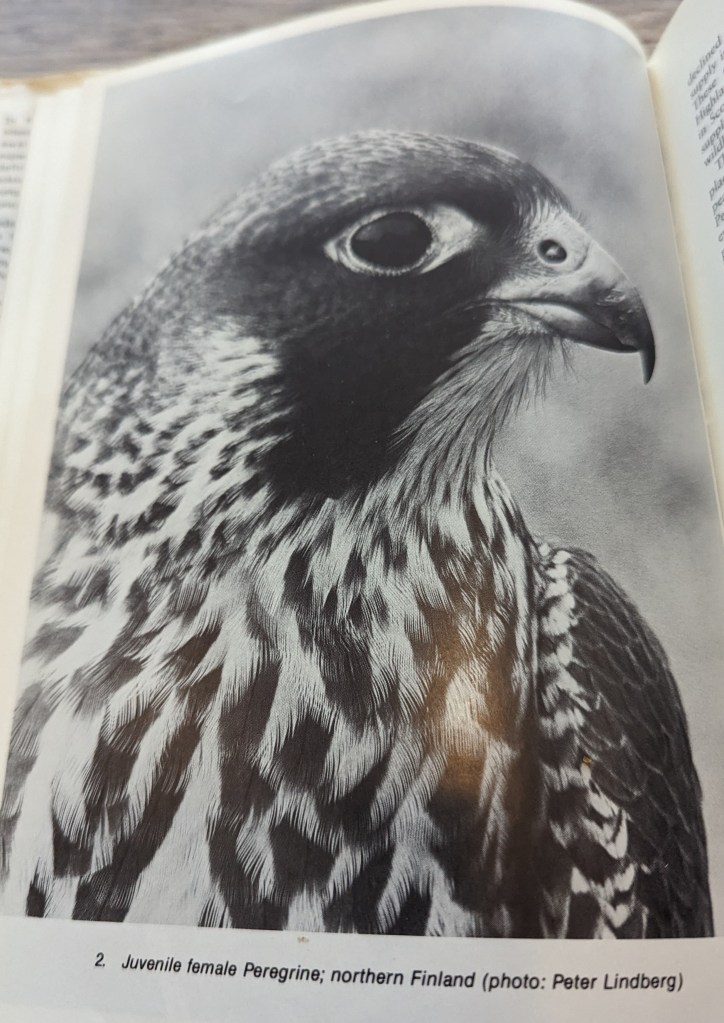

In this part of the countryside, the cascades of hawthorn are over now, their slightly feathery, petally droplets have fallen. Black crows were feeding, sharp-beak first, in the field. I would certainly like to touch their glossy feathers – I have been collecting feathers every day on my walks. If I hold the white tubular calamus, or hollow shaft of a long corvid’s plumage and twiddle it, the vane catches the light and gleams. There was a matching black horse lying down nearby and she observed me, haughtily. I might not have been brave enough to touch her.

The wet grass touched my boots – I could see, but not feel. My legs brushed past the seedheads and they tickled my shins. They touched me, I didn’t touch them. In the same patch, I was alive to the contrast between the sorrel, which I knew would be bitty like toast crumbs between a thumb and forefinger, and the emery board, might-cut-you blades of grass. I remembered how I like to slide up the sheath of the softer Yorkshire Fog, just turning to seed now, gathering a mini bouquet before spilling the seeds up in a fountain and spraying them all around. I could just ‘feel’ the imprint of it on my fingertips.

I crossed the first stile which I’ve been not hand-touching for weeks anyway, so I am practiced at that. I had to steady myself for a moment or two at the top before ‘jumping’ down off the second. Then at the next hurdle, I had to slip around behind the tree because the gate was shut. It was, I admit, impossible not to touch the trunk with the edges of myself, but I lifted my arms up as I squeezed through.

There was the familiar parp of the train as it approached the first of a ring of level crossings, making its announcement. I couldn’t touch that train even if I wanted to. I spotted the first chamomile and stooped to collect a feathery stem and have a sniff, transported back to my allotment where I grew swathes of it for medicinal purposes. It was not until the end of the walk when I scanned back that I realised that that had been a touch I didn’t even think to forgo.

I feared to reach out to the wild roses in case I dislodged their fragile petals, so that was no problem. Before I knew it, I scratched my nose because it felt like a fly was crawling there. Damn! Turns out that I’m not great at this game.

I took a detour and there were the goslings, much more grown up, motionless on mirrored water. So still were they, that I assumed they were asleep, but then a parent dipped her beak and very slowly rotated to face her brood. The sun was behind, low, and I saw a drop dripping off. Mid way, it sparkled as the light shone through it, refracting into a star as it fell. Without actively moving she sailed closer to them, the space narrowing, and then she nudged the nearest chick.

It was the second hour and others were waking up and walking their dogs: a puppy scampered towards me and jumped up, so there was a wet-tongue touch without a by-your-leave. The owner and I forgot to move to opposite sides of the path two metres apart. Not so the woman with the stick – she avoided me like the plague as we have been instructed to do.

The birds were busy weeding in the arable fields, their heads bobbing. No doubt some seeds hadn’t yet germinated. A bramble scraped my upper arm leaving a long, bloody slash. Grasses caressed me and wind swept my sweaty brow – I felt it.

I stood under an unknown tree admiring its flowers. I flipped through my mental filing system, took a photo, and then the tree seemed to go ‘here you are’ and one white trumpet floated to the ground. There it lay amongst 10s of others! I picked one up (again, I didn’t even notice this touch until I started writing this) and carried it uphill. After some time I relegated it to my pocket for later perusal and it was, ooh, 5 minutes before I worked out what had caused the stickiness in my palm.

I did find an alternative route towards the end and as I squelched through the mud (there has been no rain for weeks but was some sort of stream running down the bridle path) and surveyed the broken branches from recent winds, I instinctively stroked the burl (a knotty growth) of a nearby tree, I caught myself at it and withdrew my hand sharpish, but it was too late.

The whole thing was pretty tricky. I wanted to know if the bracket fungus was hard or squashy. I wanted to warm my hand on the wall. I was curious whether the temperature of the inside of the log was different from the outside. I would have liked to swish through the Quaking grass. However, I particularly enjoyed the newfound awareness of how much my senses interact. And I had a beautiful walk.

If you ever see something in one of my blogs that is wrongly named, please do let me know. I do a lot of research but it isn’t always easy to get it right and I would be very grateful to learn.