12.5.20

Chatting and walking at the same time

I have been talking to Shetland women about home and belonging. My initial idea was to meet up in person when I visited, but it has been impossible to go due to the corona virus, so my trip is a virtual one and my meetings had to take a different form. We chat on the phone, and while we do that, we both walk – I in Kent, England, and they in Edinburgh or on Shetland. Walking is part of the experience. We are connected in time and spirit, if not in space, and we are prepared for the ‘meeting’, so, as well as the information, thoughts and ideas we discuss, it’s interesting to take the walk itself into account.

When I spoke with one woman, she had just fallen over and cracked her knee and tooth. I was negotiating road works while she told me about what happened – six men were working in close proximity with loud machines, and members of the public were trying to work out where was safe to walk. A second woman was walking in snow on Shetland, while I was in a T shirt because it was so sunny. A third is unable to walk far at any one time due to a physical condition. We kept getting cut off, the signal breaking down, and between us we had to work out what was best: I had to be out in the open, rather than under trees; she to sit still and survey her surrounding area while we spoke.

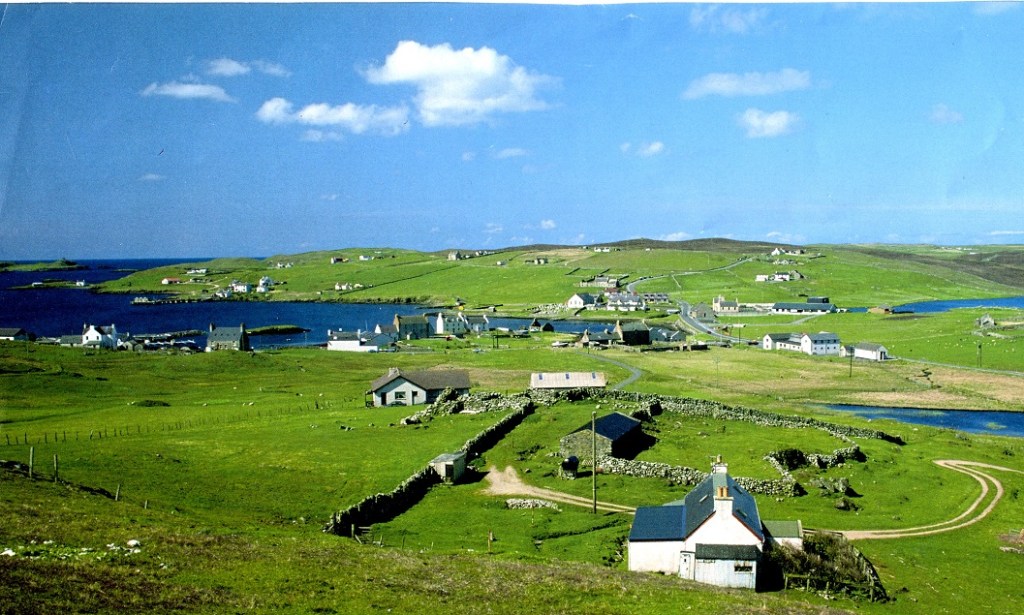

When Ann Marie Anderson phoned me from Whalsay, a jamon-shaped island in the east of Shetland, I wasn’t far from the river. Taking a right over the bridge, I passed 3 cyclists who were standing sort-of-200m apart on a path which was 1.5 metres wide, with cars parked beside them, on a very busy road. I crossed to the dangerous, non-pavement side. When I got to the Lees and climbed over a metal gate (no mean feat when you’re on the phone!) I found myself in an unfamiliar field, full to heart-height with sweeping grasses, gleaming yellow buttercups and dandelion clocks, many of which had discharged their fluff into downy piles on the hard-baked, cracked clay. I was totally alone and walked around the perimeter where someone/thing had crushed the undergrowth before me. I took occassional wee detours out and back through the bushes to where I knew the edge of the land met the river bank and found little patches of sand where the fishermen sat in days gone by. Back in the field, I deposited my anorak – an incongrous scarlet island amongst the gentle, complementary hues of nature – and traced figures of eight, winding pathways of my own in one corner as we conversed.

Walking the coast of Whalsay

Ann Marie told me about where she has lived for 18 years: how you must cross the estuary from the mainland to get there, managing the ferry terminal and traffic; how the island has around 1000 inhabitants; and that she stays in Symbister, the main conurbation, her home. ‘Whalsay is on the east coast’, she told me, ‘there’s nothing really in the middle of the island and I usually go around in a car. Recently, though, I’ve been walking around the coast, seeing it from a different angle. It’s really interesting.’ She decided to join the challenge of gathering bruck (rubbish) which has been dumped or floated in from abroad, particpating in a Shetland-wide project to pick up litter called Da Voar Redd Up. ‘There’s not a coastal path as such’, she said, ‘but little blue pointers say Access Shetland. I diverted into geos (long, narrow, steep-sided rock clefts formed by erosion in coastal cliffs) and onto beaches where I could.’ So far she is 3/4 of the way round and has picked up 80 bags. Some of the pieces she has lifted have come from as far away as Massachusetts!

How Shetland dialect contributes to a sense of identity

I am interested in how people construct a sense of their own identity, whether that’s by land, accent, or commonality of other sorts. One of the most impressive things about speaking to women from Shetland has been their use of dialect and the variations on English they employed when they spoke to me, the modulations they make for most folk, in fact, who are not Shaetlan speakers. Christine De Luca writes: ‘Shetland dialect – or “Shetlandic” – is a lively mother tongue, still vibrant and enjoyed both for its onomatopoeic quality and its classlessness.’

Christine told me a story about her aunt who died some years ago, but who never left Shetland very much. ‘She had been to the Women’s Guild, the church group for women, and a visiting minister’s wife had come. A woman who was in the Guild spoke to this lady in broad Shetland dialect. My aunt was very annoyed when she got back home – she thought it was so rude – it was a way of making the woman feel awkward, an example of the power of language to exclude or include.’

I have used some Shetland vocabulary for the landscape, birds and animals in previous blogs in this series, and in Research and Planning, you can read some of Christine De Luca’s words, written in the way she spoke them, and find links to recordings.

Ann Marie explained that she writes peerie bairns’ (little children’s) books in Shetland dialect, also working with them in school because, ‘Through my work I can see that the Shetland dialect is a dying one. A study has shown that in the next 25 to 30 years it’ll be gone. People are changing their tongue so that they are understood better and I do think that the TV has had a huge impact on that. There are still areas where it is strong, and I like to think that I’m doing my peerie bit to keep it alive so that hopefully it’ll be there in the future.’ Before the lockdown she was working alongside Shetland Arts delivering ‘Arts in Care’ workshops with elderly people in care homes. She told me, ‘It’s interesting, seeing how the children and the elderly respond differently. ‘

‘I read the elderly certain poems and it’s amazing the different directions the people from the different care homes take. For example, I read them Christian Tait’s Da Magic Stane (about a stone which is sent skimming and visits some of Shetland’s Isles). One group wanted more information on the origin of the name Papa Stour which is one of the islands the stone visits; where others started speaking about where they were born and what was going on at the time they were born, how they were delivered in the house and there not being any hospitals; how life has moved forwards.’ You can listen to Tait’s poem here.

Deepdale and Sandness Hill walk. Thanks to Alastair Hamilton for this and other information from his blog on shetland.org

Christine writes in English and in Shetland dialect which is a blend of Old Scots with much Norse influence. She said, ‘The way people identify through language and the relative status of ways of speaking is quite a complex thing. For example, my cousin phoned me yesterday. Now, she’s in Edinburgh and she was brought up in Shetland, but her father’s people were from the south…. so their home wasn’t as Shetland as mine was. She thoroughly understands it, half speaks it, you might say, so when she phoned me I felt quite comfortable speaking in my normal Shetland dialect and she would just speak back in her kind of half-Shetland accent…it comes naturally. My sister, of course we were brought up the same, we just naturally speak in our Shetland tongue. My two brothers are slightly different – my elder brother went away at seventeen, into the Royal Navy officer class where you have to speak as they might expect you to do. He is very English spoken, but when he has been with us for a bit then he speaks in dialect again.’ I asked her if it was with an English accent. ‘No, he can do it quite perfectly!’ she replied. ‘My younger brother went to Canada and married a Canadian and he speaks with a slight roll, but when he’s on his own he reverts. We are chameleons really.’

Christine: ‘We have a verb for adjusting your accent, knappin, to speak in, let’s say, an English accent when there’s no need to. Nowadays folk seem to use the verb only meaning just speaking English, the meaning has perhaps changed a bit, but it used to mean an unnecessarily English accent and it certainly had a very pejorative edge about it.’

You can listen to a recording here of the word ‘knappin’ being used in a sentence in dialect. If you’re interested, like me, in the origins and examples of ‘knap’, here is another page about it. It’s interesting that to to knap can also mean to walk in a particular way: ‘To strike (the heels) on the ground in walking (Ork. 1960); intr. to walk with short active steps, to patter, to move about smartly’, which was something I did as I passed those road works while I trying to hear the voice on the phone, but not something I could do in the field where I was talking with Ann Marie.

Here’s a Whispered reading by Still Waters ASMR of Ooricks in da Paet Hill by Ann Marie Anderson and illustrated by Jenny Duncan. The children’s book is about Ooricks, written in dialect of course, about digging peats from the bank in the traditional way. The Peerie Oorick Etsy page and the Peerie Ooricks Facebook Page

Christine De Luca’s website is here. Christine was born and brought up in Shetland, spending her formative years in Waas (Walls, see above) on the west side of the mainland, 15 minutes drive from Sandness (above). She now lives in Edinburgh. Her main interest is poetry, but she is also active in promoting work with Shetland children and has written dialect stories for a range of age-groups. In addition to this, her first novel, And then forever was published in 2011. She was appointed Edinburgh’s poet laureate (Makar) for a three year period, between 2014 and 2017. She has been published and recognised widely in the UK and internationally, wining prizes and having her work translated into countless other languages.

Christian S. Tait was born and brought up in Lerwick, where she now lives. After teaching music (Primary and Secondary) for twenty years, she was a primary teacher until her retirement in 1995. Christian writes in both English and dialect. Her first poetry collection, Spindrift, was published in 1989. Stones in the Millpond (2001) is part history and part a collection of poems inspired by and based on the experiences of members of her own family in the First World War. Her work appears in the New Shetlander and other local and national publications. Christian’s novel And Darkness Fell, set in and immediately after the First World War, was published by Shetland Library in 2018. You can find examples of her work here.

All photos are copyright Tamsin Grainger unless otherwise specified