All this week I have been in conversation with women from the Shetland Islands and travelled, in my imagination, to the places where they have lived. Two of my conversations have influenced my (virtual) itinerary: Leah (from Shetland Islands with Leah) and Christine De Luca. So, I made my way from Northmavine (where I met Helen Robertson), eastwards to Whalsay, where Leah lived shortly after she was born, and then in a southerly direction, via Lerwick where she was brought up, to Bressay which she knows as an adult, and where Christine also lived when she was a baby.

Whalsay

Whalsay is a small isle, 5 x 2 miles, east of Vidlin. There are even smaller islands between it and the mainland: 3 Holms (Wether, Score and Bruse) and 2 Lingas (Little and West). Fishing is its focus and Symbister harbour its hub. Boasting a Whisky Heritage Centre, golf course and swimming pool, my reason for visiting was the possibility of spotting sea mammals, whether from the ferry (see below) or as I hiked. I set off, anticlockwise, along the road past the Loch of Huxter and made a detour to the Ward of Hevadafield (61 m).

Back on the tarmac, I passed Nuckro Water opposite Vats Vord and once I arrived in Ibister, I curved around to Nisthouse and down to the Ness with its rocky coast and view of other outlying islands: East Linga (from ling meaning heather), Ibister Holm (a holm is an islet), Mooa and Nista. The Vikings called it The Island of Whales, so I was hopeful, but they were dashed – not today. I would, however, agree with another of its monikers: Da Bonnie Isle. Poet Christopher Grieve, aka Hugh Macdiarmid lived on Whalsay and I took a leaf out of his book and lay myself down.

‘Nothing has stirred

From On a Raised Beach

Since I lay down this morning an eternity ago

But one bird. ‘

The familiarity of one’s locality and the effect of pacing the land, can contribute to a sense of belonging. Knowing the area, recognising the landmarks and retracing your footsteps can evoke a visceral reponse. Leah said, ‘When we hike, we say, ‘Doesn’t it just smell like a Shetland night?’ It’s the freshness in the air, and then the heather and the sea mixed in there. It’s really unique, because I have been in the hills throughout Scotland and it’s different. There’s an immense sense of calm when you reach your destination. The view is mindblowing and the feeling of contentment is overwhelming. I hope that other people feel that when they come here. I don’t know if it’s just because I am so thoroughbred Shetland, so in love and passionate about where I’ve come from, but I hope that’s the feeling that people who visit here get too.’

The ferry terminal for Whalsay is at Laxo, a 20-mile drive north of Lerwick. The crossing to Symbister takes 25 minutes and the service is frequent, although booking is advised in the peak season. View timetable here.

shetland.org

Leah told me about when she was going to university in Edinburgh, how excited she was to be on the Scottish Mainland, aged 17. Her dad saw her and ‘the massive, biggest suitcase we could find in the shop’ off at the boat, and she negotiated the long journey, alone, going straight to the University to enroll and get her ID card. She said, ‘It was an overwhelming day’. Then, at the first class, she had to stand up and speak in front of the group. On hearing her, the tutor asked, ‘Where is your accent from?’ and ‘in front of everybody he said, “Is that where they still ride about on donkeys?” ‘This rude, racist, remark was not designed to make Leah feel at home or as if she belonged in her new surroundings. All such ill-informed comments separate, set one apart and, of course, belittle and shame.

Belonging means acceptance as a member or part. Such a simple word for a huge concept. A sense of belonging is a human need, just like the need for food and shelter.

Psychology Today

In direct contrast, Leah went on to describe a Shetland community event which does the opposite – welcoming and fostering belonging. ‘Has anybody told you about Sunday Teas?’ she asked me. ‘I think this type of thing originates from the fact that Shetland was the last place in the country to have TV. It wasn’t that long ago, so the only thing you had to do was socialise and Shetlanders do tend to be very social people. Everything revolves around food!’

Leah continued, ‘Through the summer months everybody bakes and they drop it off at the hall, and between 2 and 5pm, you go, pay at the door, and there’s an absolute spread of homebakes … you fill your plate, get your cup of tea and sit with whoever. It’s not tables of 4, but of 8, and you all sit together, have a chat. People will drive, for example, from Lerwick to Bigton in the south end, or Bixter out west (Aithling), both 20 minutes or so drive. Every week they are advertised in the local paper and everyone goes: from new born babies to 90 year old women. We don’t have ball pools or private nurseries or bowling, so the community halls are used for toddler groups; Friday night take-aways; anything and everything. It’s all done by volunteering, so you’ll get your pinny on, you’ll serve tea and sandwiches, there’s no airs and graces, everybody is equal in a community hall, mucks in, helps out and has a good time.’

It sounded to me as if going to the Sunday Teas would not only situate you in a place and a group where you can belong, but by engaging regularly with others, it is tantamount to saying, ’Here I am, I am part of this group, I belong, want to be let in and recognised as part of the community’. These halls and events obviously fulfil a vital role.

Isbister (Whaley)

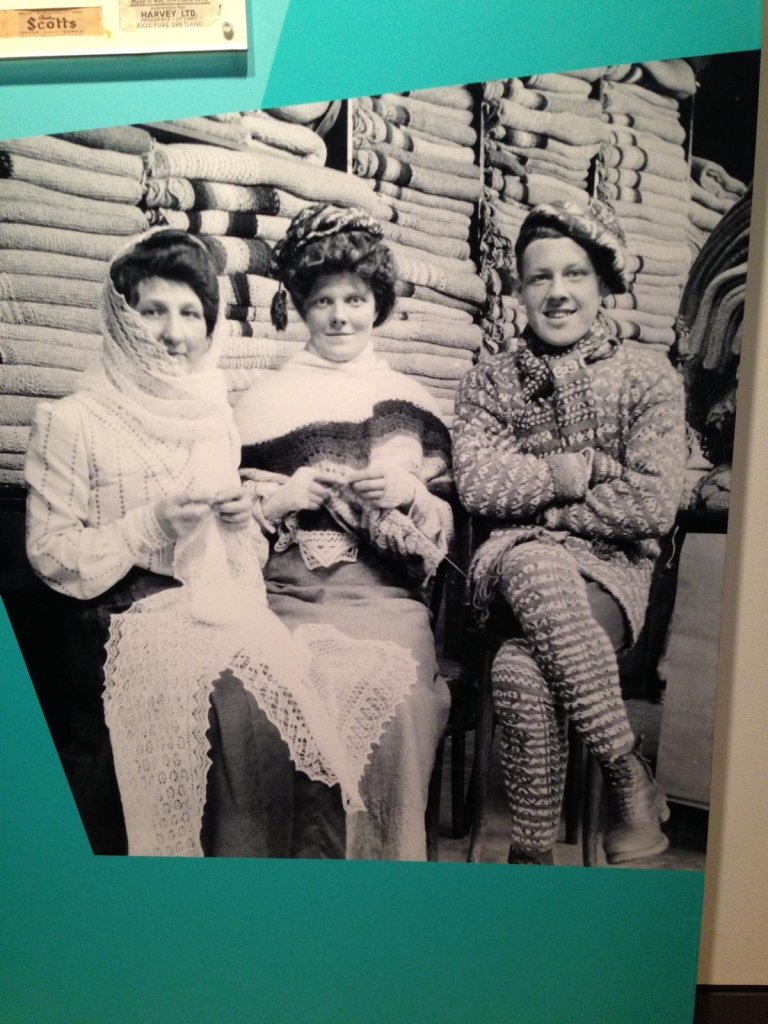

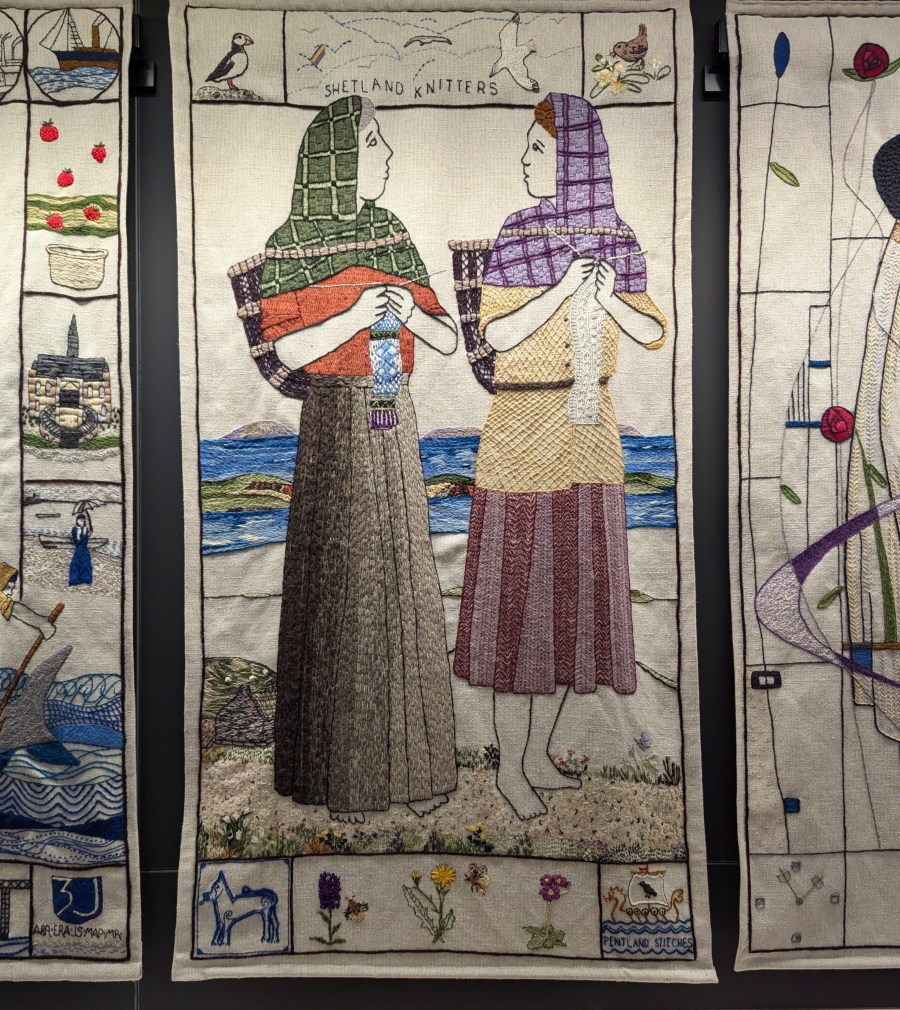

“In rural communities all over Scotland, women worked hard doing menial, muscular tasks. They did the back-breaking work of weeding, shawing, milking and bringing fuel for the fire. This image shows two sisters with creels on their backs. They chat as they walk, knitting without a glance at what their practiced fingers are doing.” from The Great Tapestry of Scotland #115

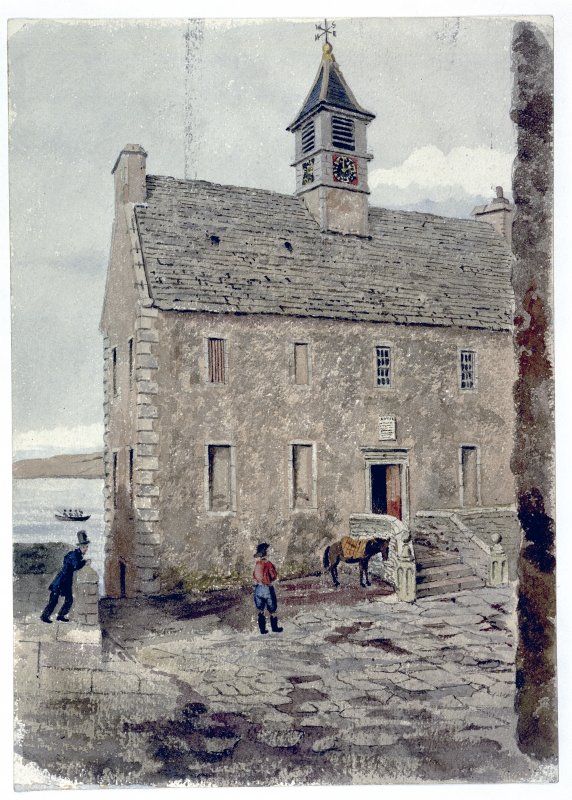

Bressay

Bressay is also on the east side of Shetland, further south than Whlasay. Only very slightly larger, it is a mere 2.8 miles (4.5 kms) from Lerwick, taking 7 minutes on the ferry! Boasting a Heritage Centre, restaurant and post office, it is the Speldiburn cafe which attracted my attention.

Plastiglomerates are, ‘evidence of coastal change. A proposed new kind of ‘human-made’ rock, plastiglomerate consists of a mix of melted plastic debris and natural sediment, and samples have been found on shorelines across the world. These uncannily organic forms are however but a visible part of a terrifying ocean plastic pollution problem.

from AL’s website

As well as food and drinks, there is a good-as-new shop, community lending library, a multi court for kids to have a kick-about, a bulky waste recycling scheme, and upskill and re-use projects. It is run by volunteers from the not-for-profit group who took over the old school premises, and like a lot of similar organisations during this Covid-19 crisis time, it is currently making food for delivery or take-away. There are also art and craft studios here, an exhibition space and Aimee Labourne’s workshop.

Wildlife on Shetland

Video of otters in Shetland from Britannica. Billy Mail andMolly, a Shetland otter in the National Geographic Review The Guardian.

Once again, I make a bee-line, on foot, for the coast. With a promise of otters, I could barely contain my enthusiasm to leave the towns behind. Part of the weasal and badger family (Mustelidae), apparently Shetland has the highest density of otters than anywhere in Europe and I understand that Brydon Thomason is the go-to man for a tour and any information about them. His website is here.

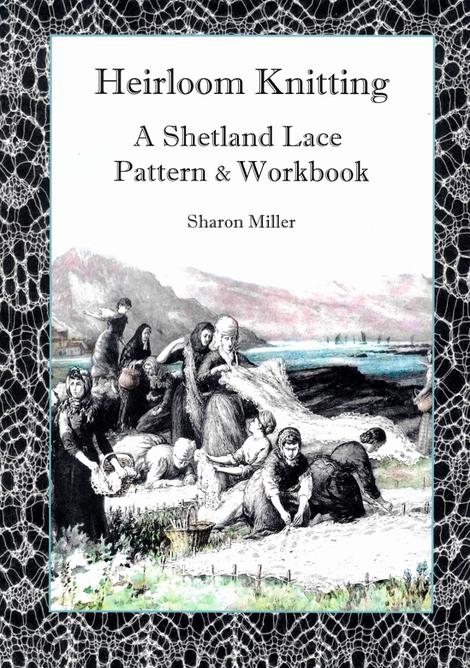

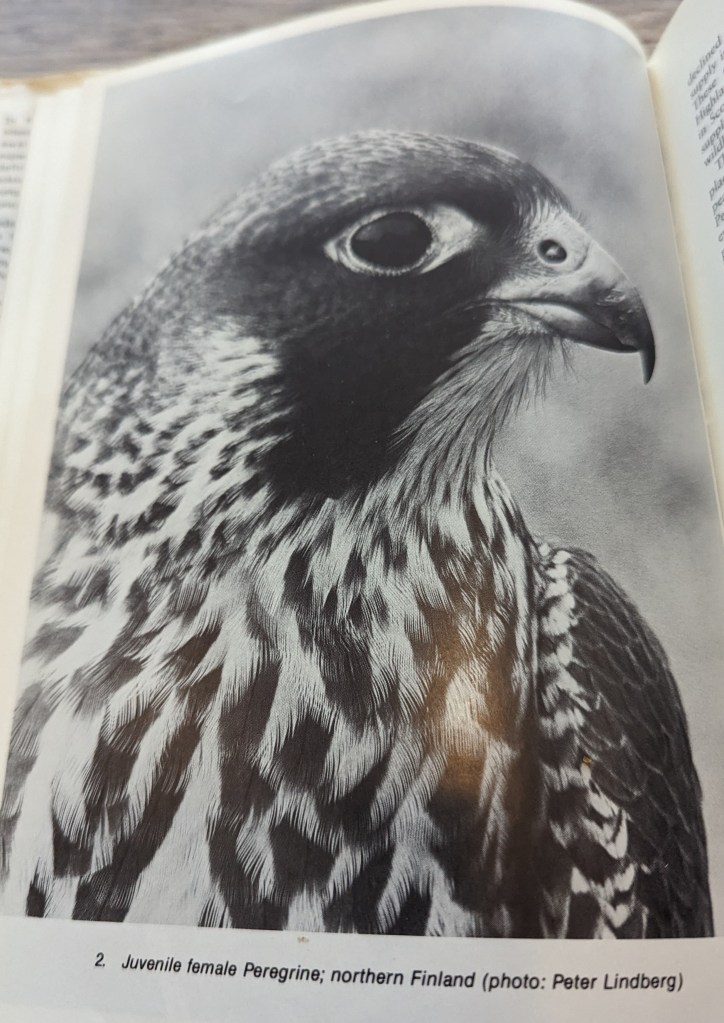

Peregrine falcons have a history on Shetland and in his book, The Peregrine Falcon, Derek Ratcliffe states, ‘Shetland … another complex archipelago, with a huge total length of of highly indented coast, much of it rock bound. … Saxby in 1874 said that many pairs still remained to breed and that there were several on Unst. Evans and Buckley in 1899 wrote that they were ‘distributed pretty commonly’ over the Shetland group. The Venables wrote in 1955 that they knew of 11 breeding pairs …’ They are now a protected species in Scotland, and have been seen in Shetland (2025).

On Shetland, a puffin is known as a tammie norrie and an otter as a dratsi.

Personal History

As I walk, I reflect on my own history. I remember, several years before I actually left home, how ready I was to run off across the fields and see what was over the hill. I went to college in London as soon as school ended, and straight to Edinburgh after that. Although I stayed some years in the Forest of Dean (Gloucestershire), Bristol (England), and Cardiff (Wales), I have now lived for over 35 years in the so-called Athens of the North. I don’t think I knew, when I was 18, that this would mean I would never really belong anywhere again – not English, except by birth, not Scottish because I wasn’t born there – that might be why I was so sure about voting to stay in Europe, somewhere that encompassed both places but gave me an overall identity – and why I feel our leaving the EU so keenly.

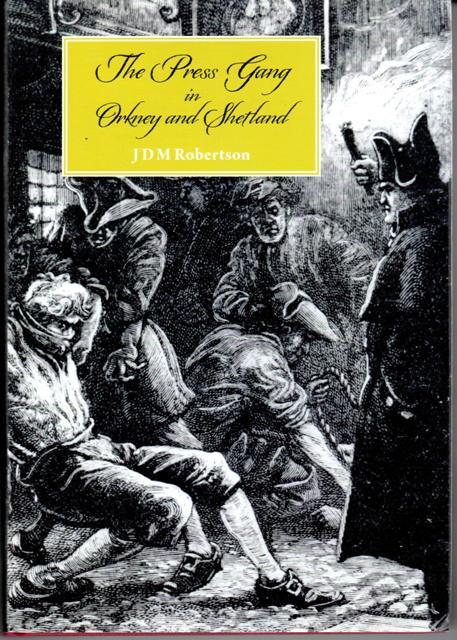

History

Shetland was incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1707. Earlier in its history, it was inhabited by Neolithic farmers (3000BC), invaded by Vikings (around 800AD), and given to Scotland in lieu of a dowry for a Danish princess, (1468 James III and Margaret (see above)). Being a fishing community, membership of the EU is a double-edged sword for Shetland. On the one hand, ‘Leaving’ promises ‘unfettered access to some of Europe’s richest waters’ (Peter Geoghegan, 2017 Northern Exposure: Brexit reveals Shetland split accessed online 10.5.20), and on the other, ‘Staying’ will result in the withdrawal of European funding for projects such as the new fish market in Lerwick which is due to be completed this Spring. In the end Shetland narrowly voted to remain (6907 to 5315 with a 70% turnout Shetland Times).

Leah seems to have two homes now: ‘After university I came home and stayed with dad for a few months, but after you’ve not been in the family home for 4 years it can be a bit tricky, so I rented a little house in Bressay. It took me a while to adapt to it, I didn’t really feel at home for a long time because things had changed so much … on top of that, all the girls who had stayed in Shetland and hadn’t gone to university had settled down, got engaged and started families. I couldn’t just pop along and see all my friends who were still in Edinburgh. I felt quite out of place, and it took me a while to find out, discover who I was as an adult. Even though I’m from here I had to put in a lot of effort to feel part of Shetland again.’

An introduction to Shetland’s history

‘Belonging’ is a fascinating and tricky subject, one that I and other writers seem to repeatedly reconsider. Wendy Pratt writes about the Mesolithic Star Carr people who once visited Paleolake Flixton in Yorkshire at regular intervals. This ancient, now almost-lost body of water, is the titular Ghost Lake of her new book. The Star Carr people were nomadic (as most communities had to be back then) and she writes that they, ‘must have had a mutable sense of belonging and home. … The ritual deposits of hunting masks [found during an archeological dig] and the careful building of roundhouses have an edge of permanence. And in fact they were returned to, fixed and improved year on year. Perhaps ‘home’ for the Star Carr people was multiple, … That is a kind of belonging.’ (p5)

This speaks to me, having lived a modern, nomadic life for a while, and this virtual visit to Shetland throws a whole new light on ‘a sense of belonging’. Is it possible to feel that you belong somewhere, even if you’ve never actually been there? Does a deep engagement with place, even on a virtual level, allow you to feel a member of that community? What do you think? Please comment below if you would like to.