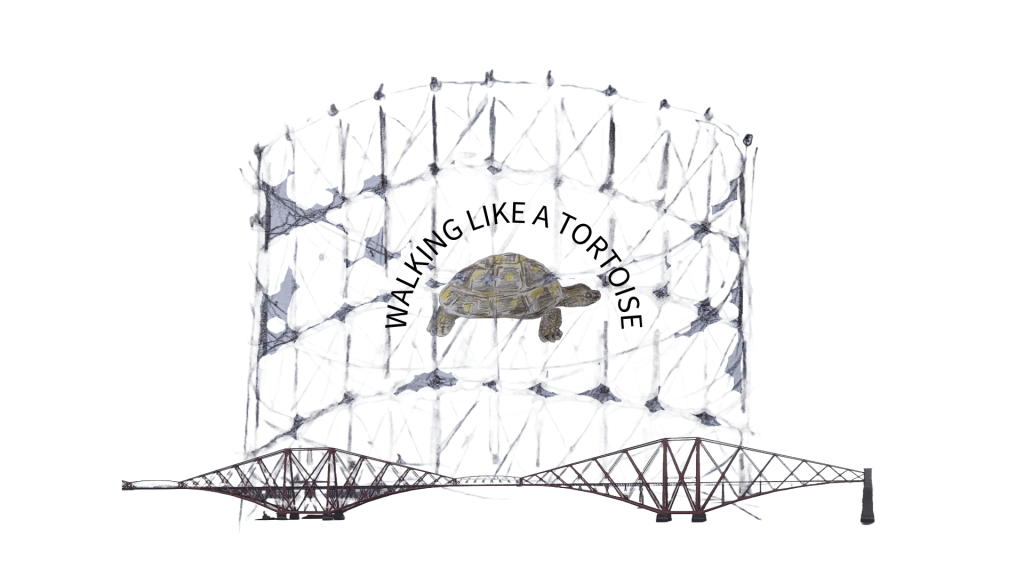

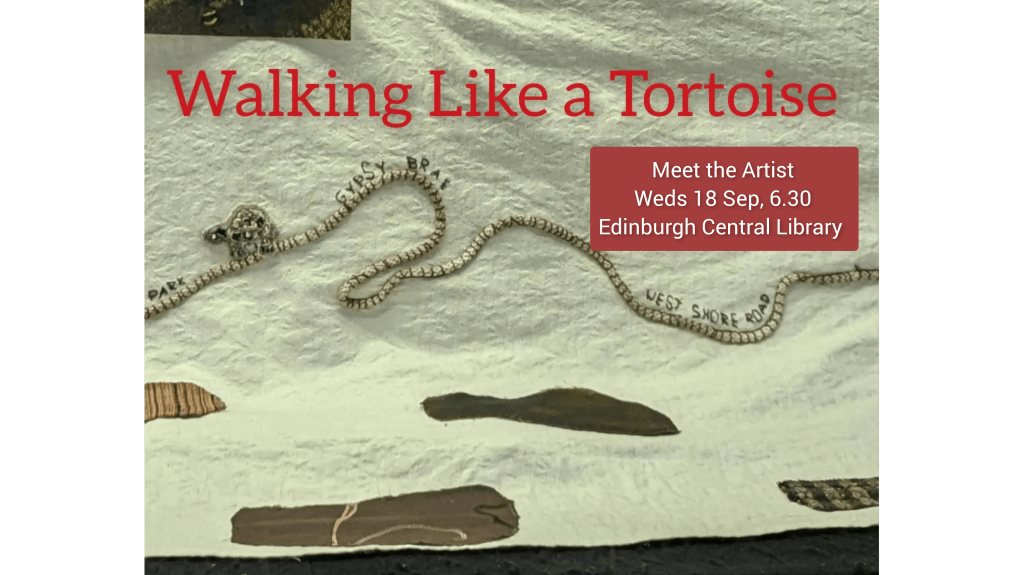

Walking Like a Tortoise around the Granton boundary

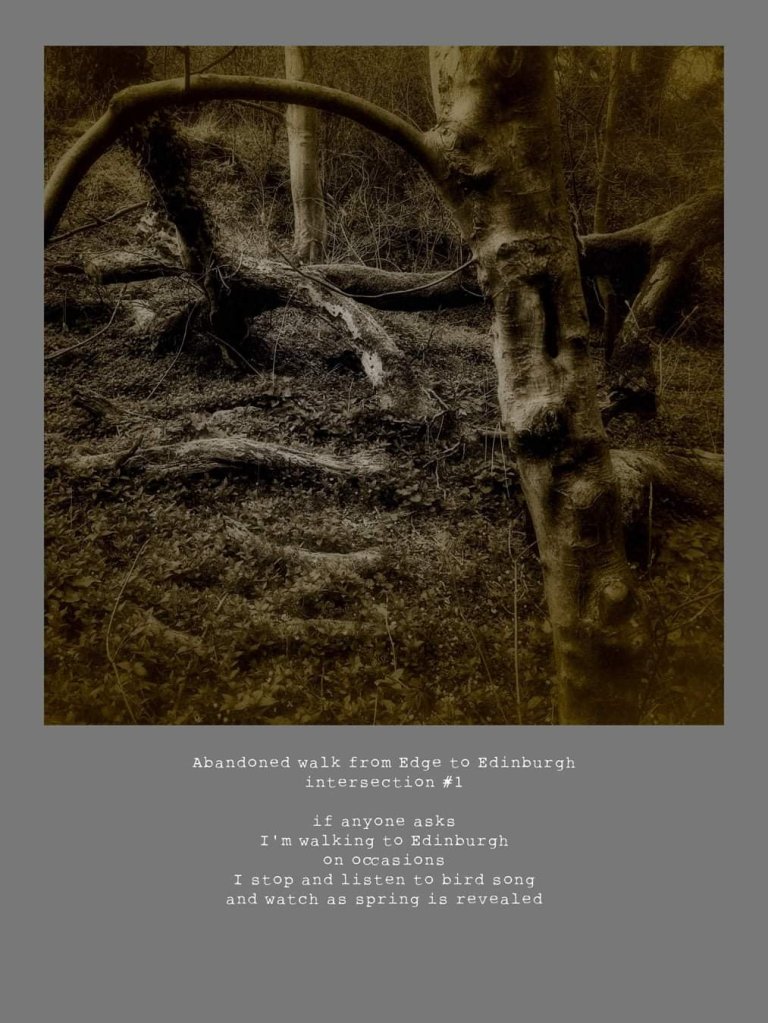

This project started with a collective walk on the Festival of Terminalia on 23 Feb 2023. It was followed by further solo and group walks and became the Walking Like a Tortoise project, which incorporated mixed media art exhibitions at Granton:hub (Edinburgh) on 29 September 2023 – 1 October 2023; Granton Station; Spilt Milk Gallery (online); and Edinburgh Central Library between 1 August – 30 September 2024. Community walking and workshops were a key part of this project and attracted a Creative Scotland / City of Edinburgh Council grant. Please also see this post for further artworks

Before

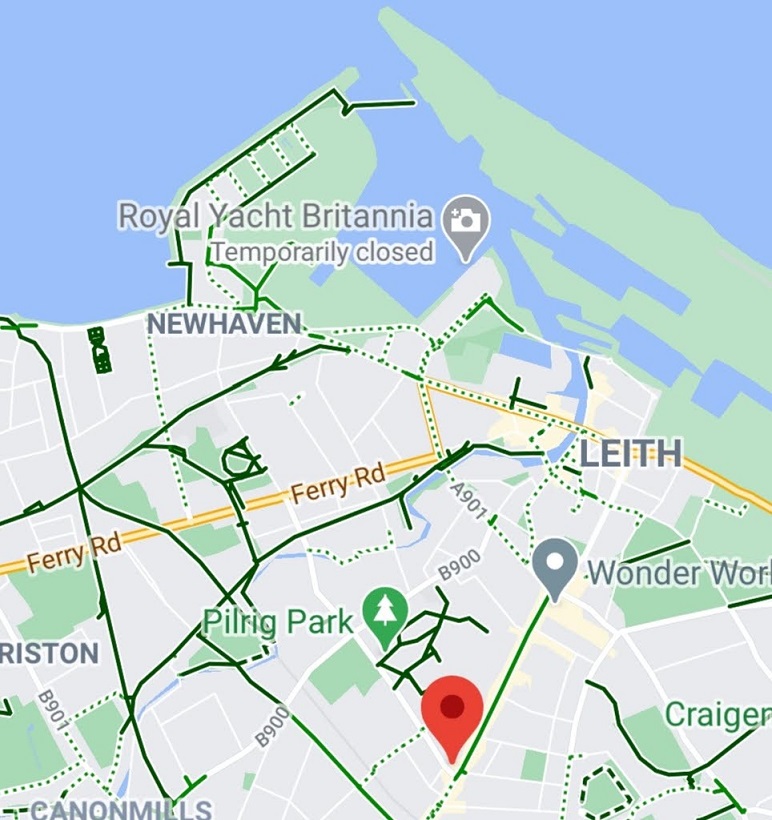

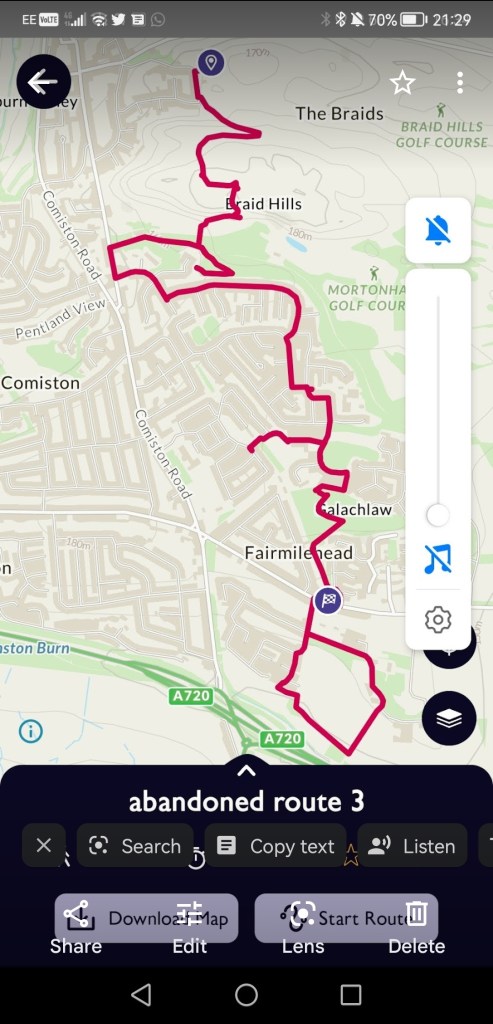

Granton is changing a lot and very quickly. My plan was to make a series of walks using different contemporary and historical maps to explore the edges of the place and document who and what I found there. I was interested to see where the area began and ended, and how it bordered on its neighbours. I was asking, Who or what is in and outside the boundary?

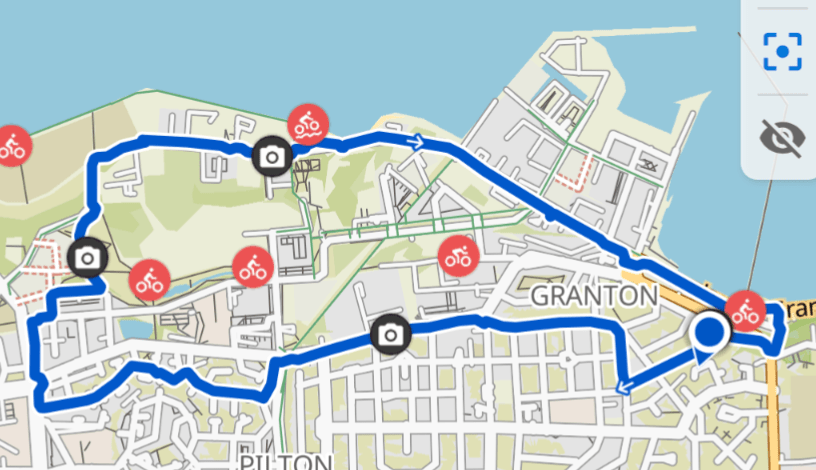

For the first walk, I set off in a clockwise direction, following the map I photographed at the National Galleries presentation of their new project, Art Works, at the Edinburgh College in June 2022:

- From Granton View, I started down Lufra Bank

- turning right up Granton Rd and right again onto the cycle path

- coming off at Pilton Drive, and walking westwards along Ferry Road

- continuing down Crewe Rd North, back towards the sea

- turning at the ‘new’ gas building by Caroline Park

- making my way along Waterfront Ave to the harbour (I knew that access to the boundary had been cut off here and that the Western and Eastern Breakwaters were not connected by land but by the Firth of Forth rushing between them, so I had to take a detour)

- along Wardie Bay beach

- climbing up Wardie Steps to the post box

- and completing the circle back at Granton View.

I met residents and visitors to Granton as I walked and had some interesting conversations about where they thought the boundary was. I asked permission to take their photo and keep some basic information about them (name, age country of origin if appropriate etc) explaining I might use it for an exhibition in the future.

The Tortoise

The title for this project comes from two sources. The first was a charming story I was told by my former neighbour, Betty, about how as a child she was handed a stow-away tortoise from the depths of an esparto grass boat that had put in to Granton Harbour at the bottom of our road. (Esparto grass was imported for the paper-making industry in the 1940s). The second is related to the Taoist practice of ‘walking leisurely like a tortoise’ which I and other T’ai Chi enthusiasts do as a mindful meditation. When we do that, something fascinating happens: we feel part of what’s around us and also separate; we are conscious of everything—the details as well as the bigger picture—and aware of our own feelings at the same time.

I practised a version of this slow walking around Granton as a counterbalance to the pace of life around me. It allowed me to meet other residents in a relaxed way, notice what lives here, and have time for reflection and reassessment, which is something that rushing does not.

“How much are we missing because we are constantly on the go….? When will we make space for our bodies to reflect and for our hearts to widen so we can connect with who we are?”

Trisha Hershey, Rest is Resistance

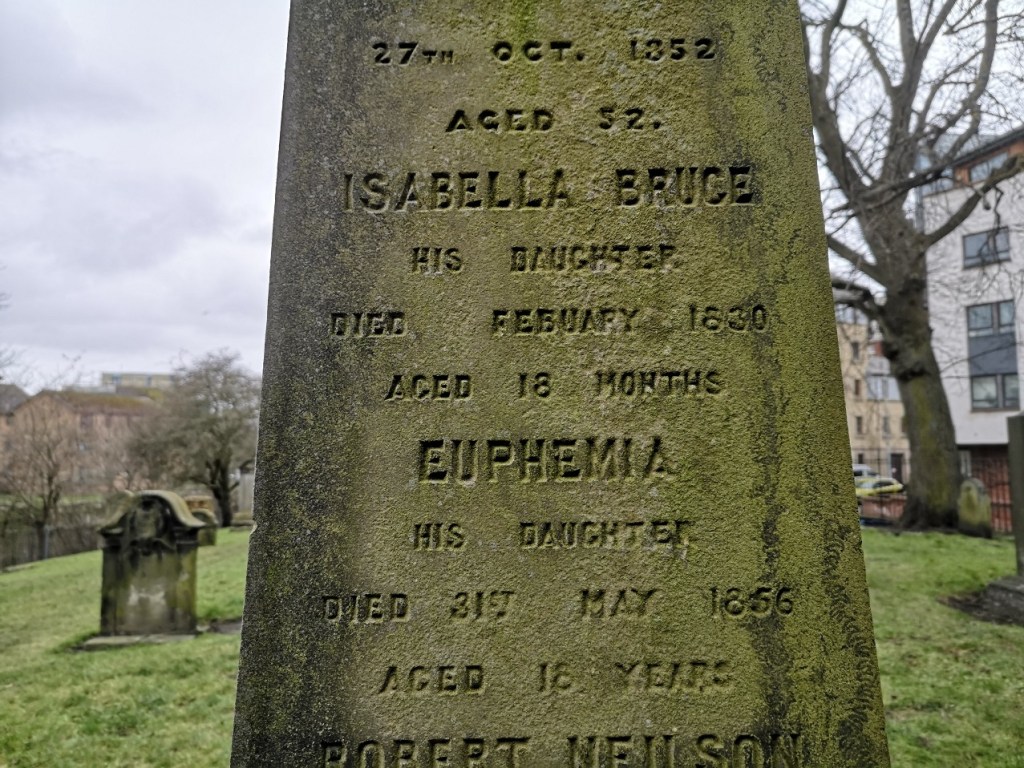

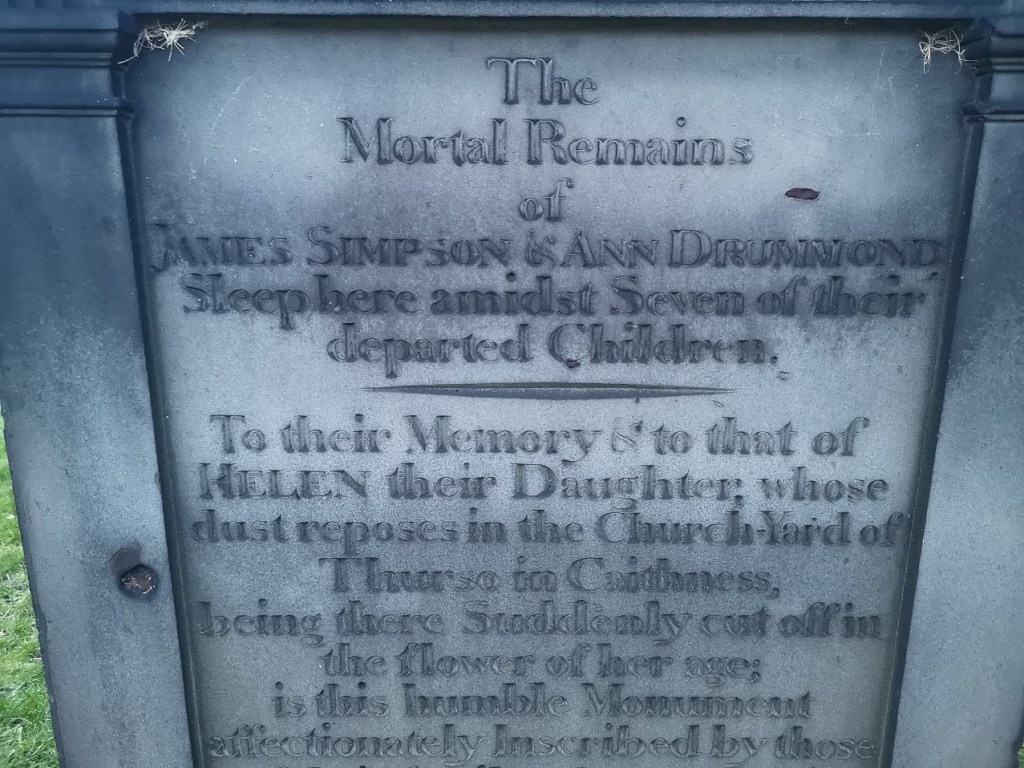

The project aimed to contribute to our collective memory by asking: ‘Where is the boundary of Granton?’ ‘Is it important that things stay the same or are changes welcome?’ ‘Is the decision-making process which is precipitating these changes a democratic one?’ and, ‘Is belonging somewhere important to a sense of identity?’

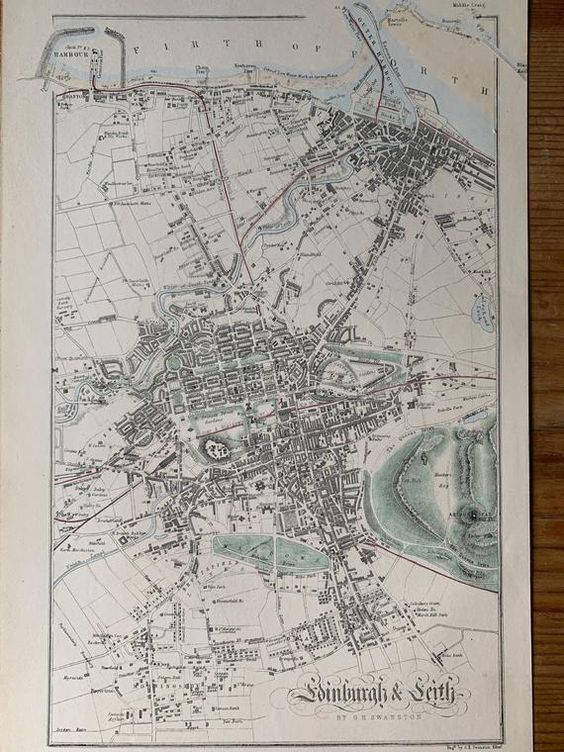

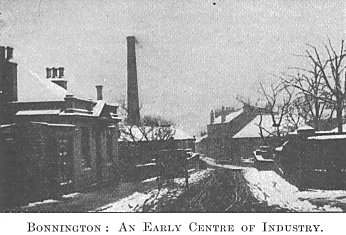

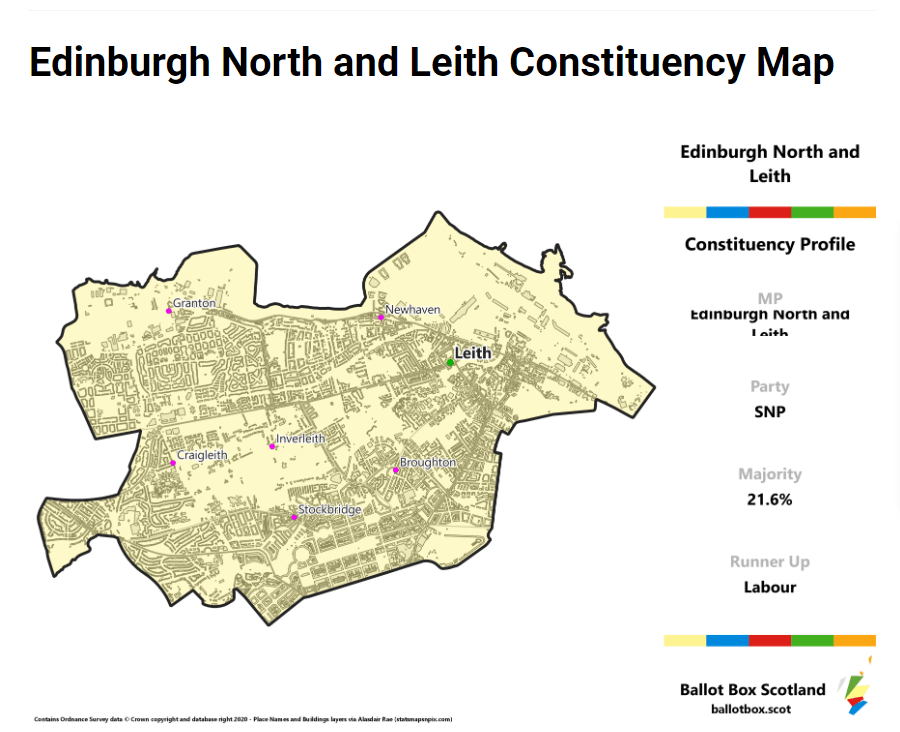

Once, Granton was outside the main city and shown in a ghostly grey on the plans. Once, there was no harbour, no outward reaching / welcoming arms from our shores. Later, Granton was part of Crammond, a large and sprawling geography which contained parts of the River Almond, Newhaven, Inverleith, most of Ferry Road, swathes of Leith, and Davidson’s Mains. It has got smaller over the years, halved and subdivided.

Maps

‘Walking like a Tortoise’ became the title for two mixed media art exhibitions based on the Granton walks. The introduction explained that I had used maps of the area from 1870 to the present day, skirted the urban and coastal landscapes of Granton, looked into hidden corners, viewed the architecture from unlikely angles, and spent time meeting those who live and work there.

I showed a lot of Granton maps in the exhibition, the ones which were used to plan the walks, and others which showed exactly where the area was and is according to different political and social groups, and in different eras. Granton is part of entities of varying sizes and shapes and it’s not always easy to know where the dividing line is between it and its neighbours – Pilton, Wardie and Trinity. There is ‘Edinburgh North(ern) and Leith’, the Scottish parliamentary constituency, and also the Westminster (UK government) ward of ‘Forth (Edinburgh)’. Then there’s the Edinburgh Parish of which we are part, the EH5 post code area, or the more generic ‘North Edinburgh’. Each map charts different distinctions and definitions which serve to separate and unify people and places. They are always political and prompt the question, ‘Are you in or out?’ Like all maps, they are networks; a tracery of streets and cycle tracks which lead to somewhere important. I walked these pathways and discovered that though they sometimes connect with each other, they are sometimes dead ends offering privacy, but no way through.

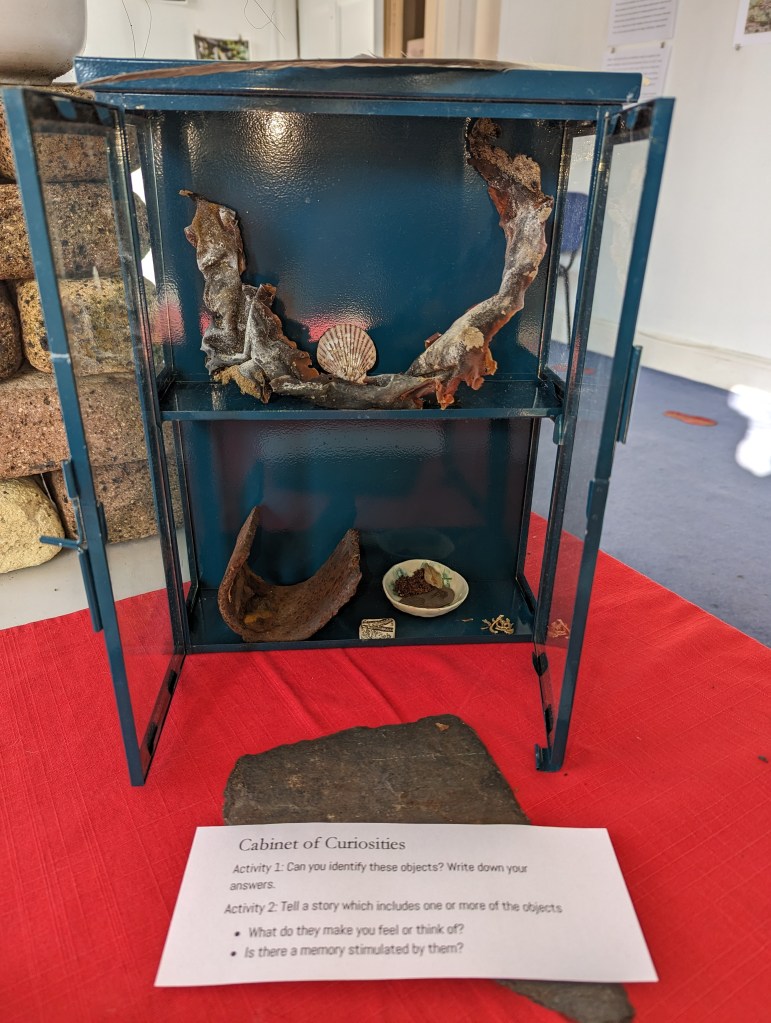

Through photographs, words, textiles and found materials, I asked how the act of slow walking can develop a sense of belonging somewhere, and how mindful noticing of the area, on foot, promotes appreciation of, and connection to what is home. Then the official boundaries are less important and it’s the human and natural links that matter.

New Building

The Granton, Royston and Wardieburn schemes (social housing estates), which started being built in 1932, have long been demolished and substituted. Much older, formerly industrial buildings have also been raised to the ground, and now green / brownfield sites have been replaced with tall, rectangular boxes of oddly coloured bricks with little history and no gardens (although some advertise dog grooming facilities). All this is despite Historic Environment Scotland stating, “The historic environment shapes our identity. It tells us about the past, the present – even points the way to the future.”

Planned at least as far back as 2019, it’s only recently that the Council, an hour’s bus journey away in the middle of the city, actually embarked on further extensive apartment building out here at Edinburgh’s edge. Although the architects and planners who spoke at a recent Pecha Kucha public event (EDI- v.45: RETROFIT “The greenest building is the one that already exists”) were unanimous in agreeing that changing existing buildings is infinitely better for the environment than putting up new ones, these newbuilds are now happening apace.

Slow

Walking slowly around and hearing people’s stories helped me and those who walked together in the community events feel part of a multi-cultural community. We found that we all have different backgrounds, but share a need to belong somewhere, that there is something unifying about how we live and use our local resources. Going to one of the Co-op stores slowly on foot is a chance for us to catch up on news; the Granton Community Bakery queue is ideal for some lively banter; returning your book and using the computer at the precious Granton Library offers time to listen to and exchange local gossip, securing community ties; and scything wheat in the Granton Community Garden followed by eating lunch together is a choice opportunity for swapping experiences.

Slow is “a position [that is] counter to the dominant value-system of ‘the times … We believe there is a positive potential in slowness as a means of critiquing or challenging dominant narratives or values that categorise contemporary modernity for many”.

Wendy Parking and Geoffrey Craig, Slow Living

Collaborations

The first Walking Like a Tortoise Community Walk took place on Friday 29 September 2023, followed by the opening of the exhibition at Granton:hub. Granton:hub is the home of the community archive where I volunteered and worked for 6 months during this project, meeting members of the public at the weekly drop-in sessions, sharing community walks, an open day, and art workshops, some with members of the Granton History Hub and volunteers.

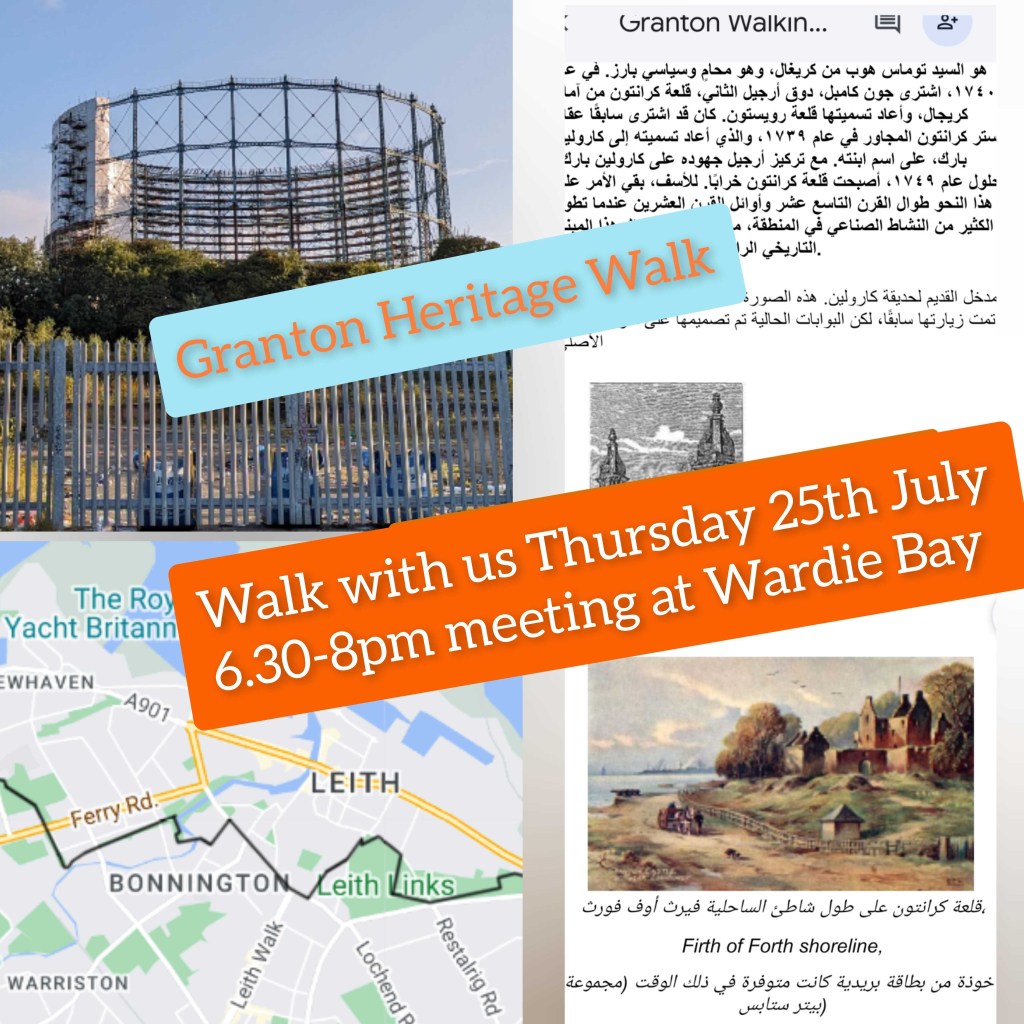

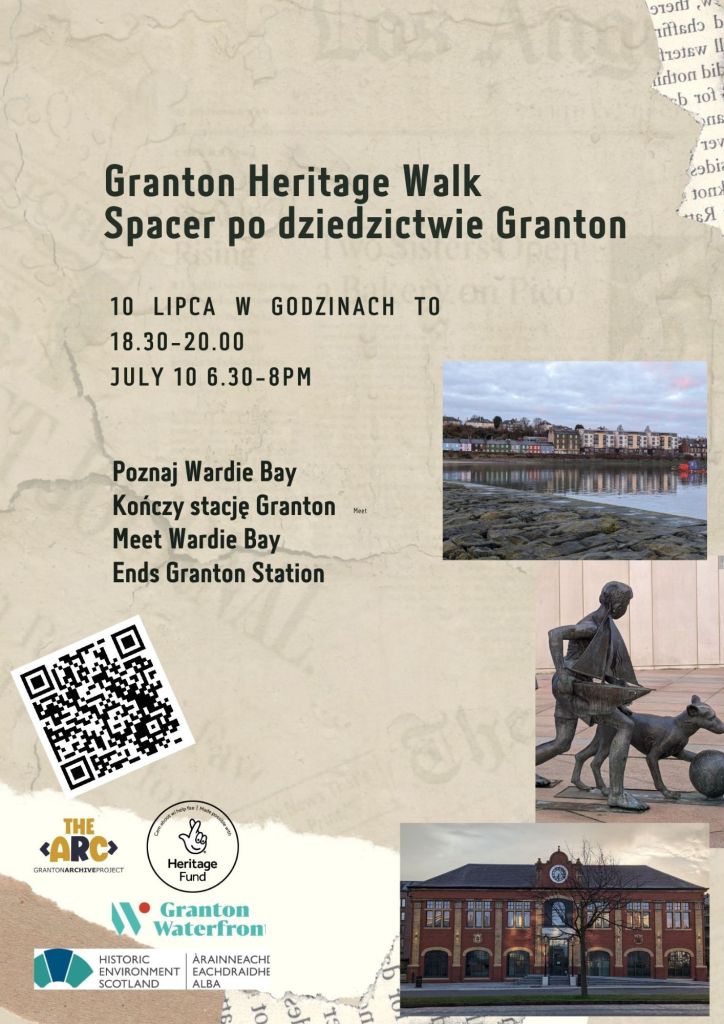

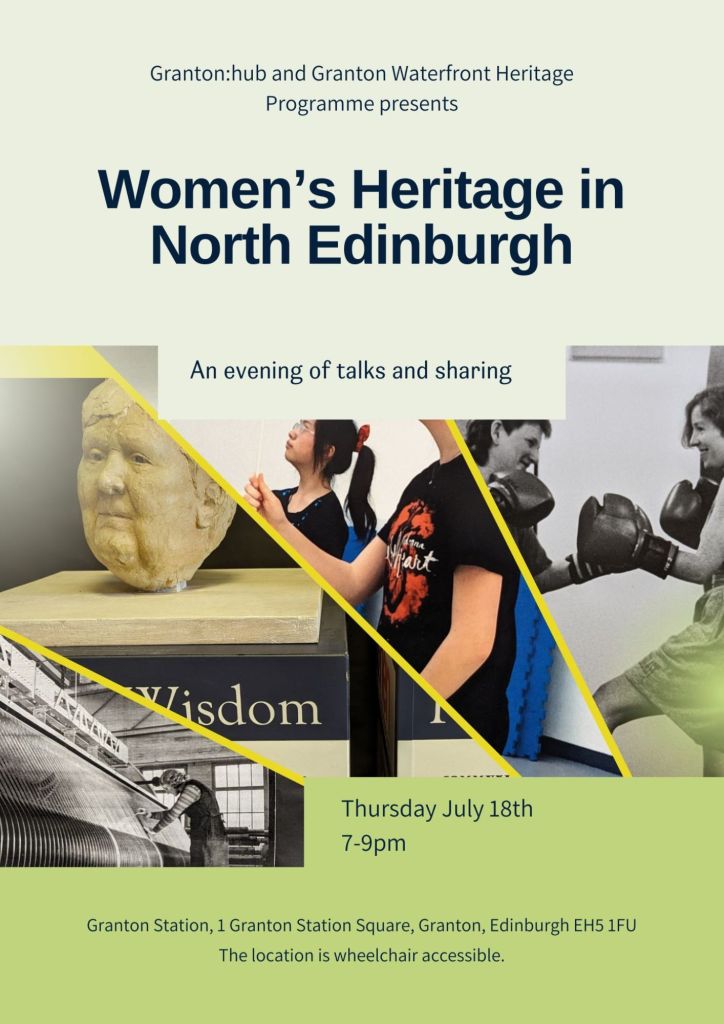

Granton Waterfront were also funders of part of this project, incorporating more community walking and including translations of the text into Arabic and Polish, art workshops for children and for adult carers, and an evening of community sharing and discussion – Women’s Heritage in Granton and North Edinburgh which focused on Black women and women of colour and involved Edinburgh and Lothians Regional Equality Council (ELREC), the Edinburgh Carribbean Association, and Project Esperanza. This project was also involved in Cultural Heritage at the Metropolitan Edge (CUMET), with Granton:hub and the Edinburgh College of Art.

A children’s workshop was held at the Edinburgh Central Library on 14 September (see below). On 18 September 2024 there was an adult event: a tour of the exhibition, a slow walk (like a tortoise – a style of marital art), an explanation of the project in the context of geography (counter-mapping), anthropology and the changing population from the past to the present, and an author/artist reading from The Wall (short-listed for a Sound Walk September Award).

I have now circled these roads and byways many times, and as a long-time Zen practitioner I always aim to walk without expectations of what I may find, to be in the moment. I’m ready to encounter and notice what arises. Though I’m a psychogeographer, I resist straying if my interest is piqued, sticking instead to the prescribed boundary route, but taking care and paying equal attention to the urban and the rural, the so-called banal and the beautiful.

There were more questions arising from the Walking Like a Tortoise project

The City of Edinburgh Council have sliced off the coastal strip and named it Edinburgh Waterfront. Does that mean that we need to let go, then, of that fragment of Granton and accept that our border is now an inland one, that we have no seaside?

The Council have also renamed buildings and streets, disorienting older, local people and confusing their memories. Was this necessary? Did they take care to think it through or were considerations of image more important?

Granton has no equivalent of the Leith ‘Persevere’ emblem, and I took to thinking about and discussing what one might look like. I wondered whether the tortoise could be part of it. What do you think? What else could we add to represent our community?

Tensions

There are tensions at this edge of Edinburgh. A young Chinese woman told me about her feelings of loss over the cutting down of trees overnight to make way for new blocks of flats, despite the fact that the previous day she and other residents had chained themselves to the railings to make it very clear they were opposed.

Flora and Fauna – Heritage

I walked to the fringe, to the beach and wastelands at the border of Granton where the best wild herbs grow for foraging, and where there is hidden art. I diverted into the centre where the library and health centres, homes for the elderly, and clubs for young people are. I wrote about it on Caught by the River magazine. Places transform all the time, but it became plain that the alterations that people and the climate have wrought on the built-up environment and natural spaces are happening at a rapid pace; there are new no-go areas, streets and stations with new names, and views which have disappeared.

Slowly wandering the boundary and making artwork has stimulated a deeper understand of local history and heritage, but how much of this will have soon vanished?

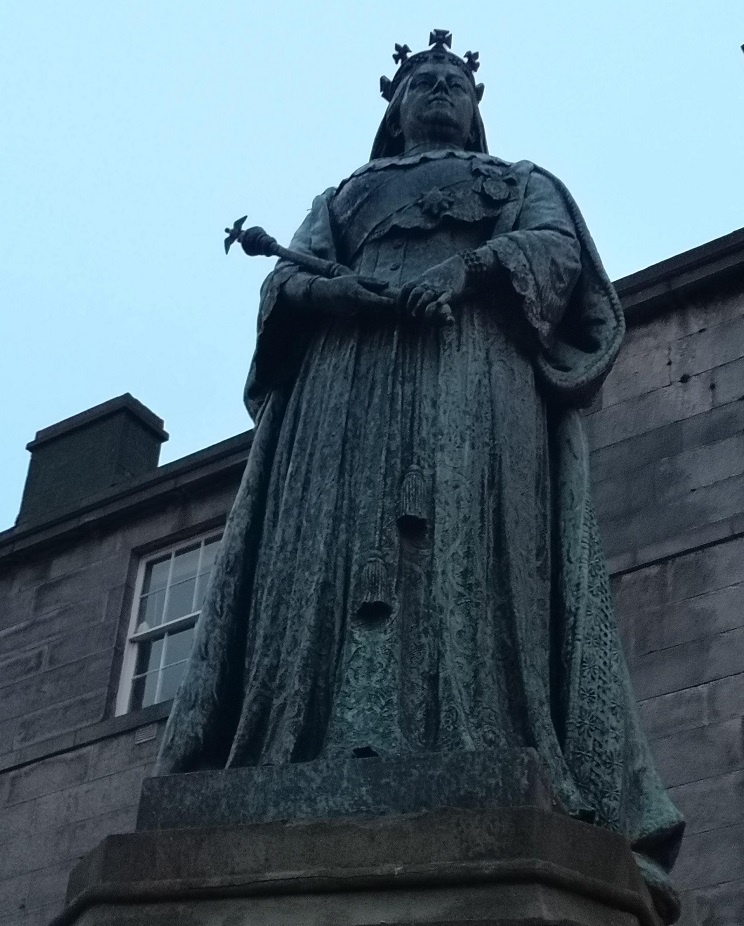

Secular, Urban Pilgrimage

I often make secular pilgrimage in places previously unknown to me, and though Granton is familiar territory, it is nevertheless a pilgrimage of sorts. As with the St Magnus Way, I left home, visited venerated places, and returned to my doorstep. There was no triumphant arrival, just a simple home-coming. It was, however, inevitably a sort of transformation – for the landscape through which I travelled, for the other human and more-than-humans (plants, birds, animals) I met along the way, and for me. After all, any stepping changes a place and it’s inhabitants.

“Seekers of wisdom, seekers of life.”

Lailah Gifty Akita, Pearls of Wisdom: Great mind

Walking Like a Tortoise at Edinburgh Central Library was supported by VACMA (City of Edinburgh and Creative Scotland)

Links to other boundaries and borders projects and the Sound Walk Map (Edinburgh):

Festival of Terminalia (official website)

The Festival of Terminalia zine is available by post for £4 plus p&p. Please email tamsinlgrainger@gmail.com

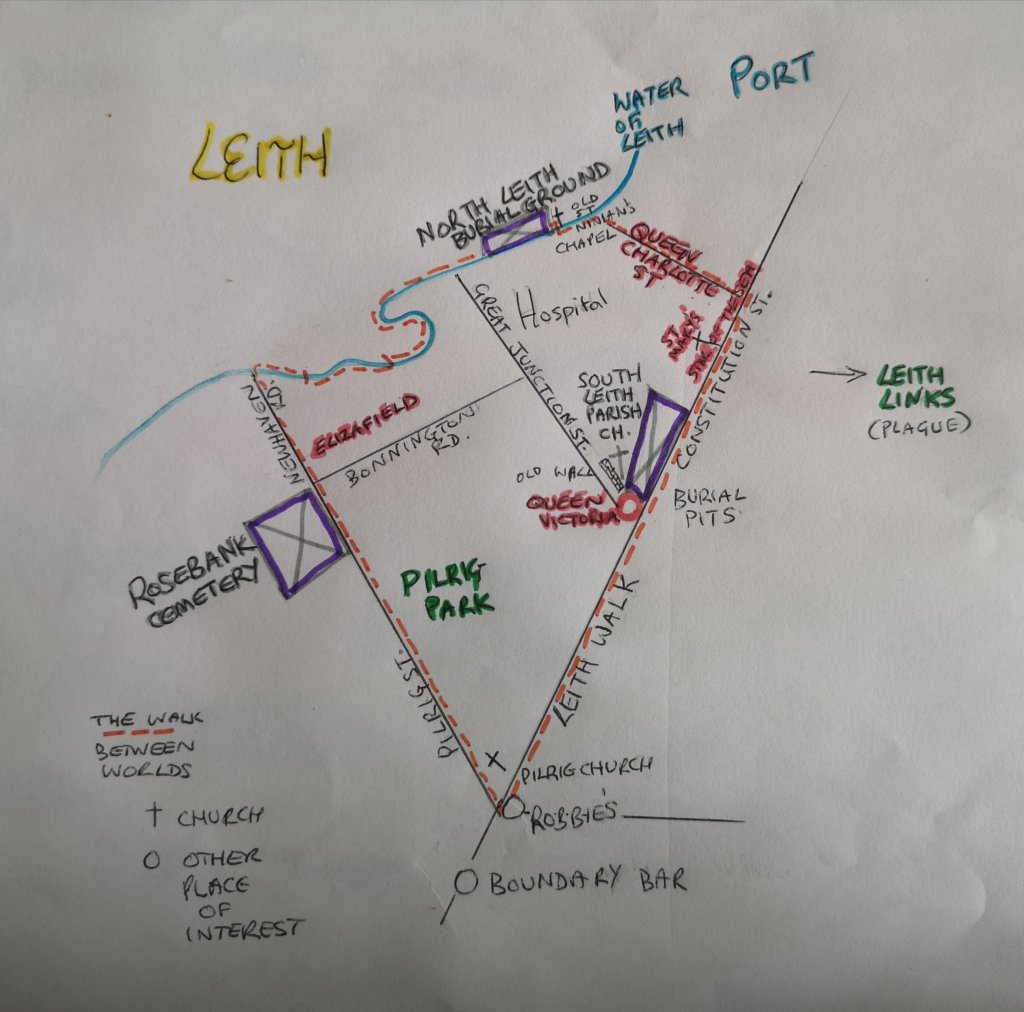

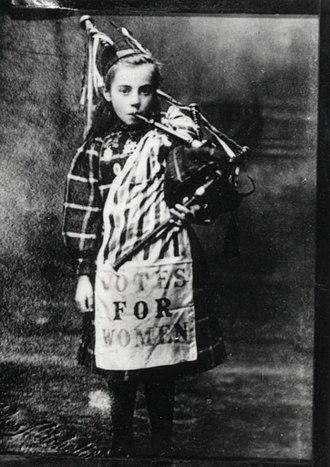

Leith’s Women and Walking Between Worlds

Festival of Terminalia (my blog)

Sound Walk Map (Edinburgh) A link to a map which shows the locations of my three site-specific sound walks: The Wall, No Birds Land and Is There a Place for REVOLution or Peace and Biscuits