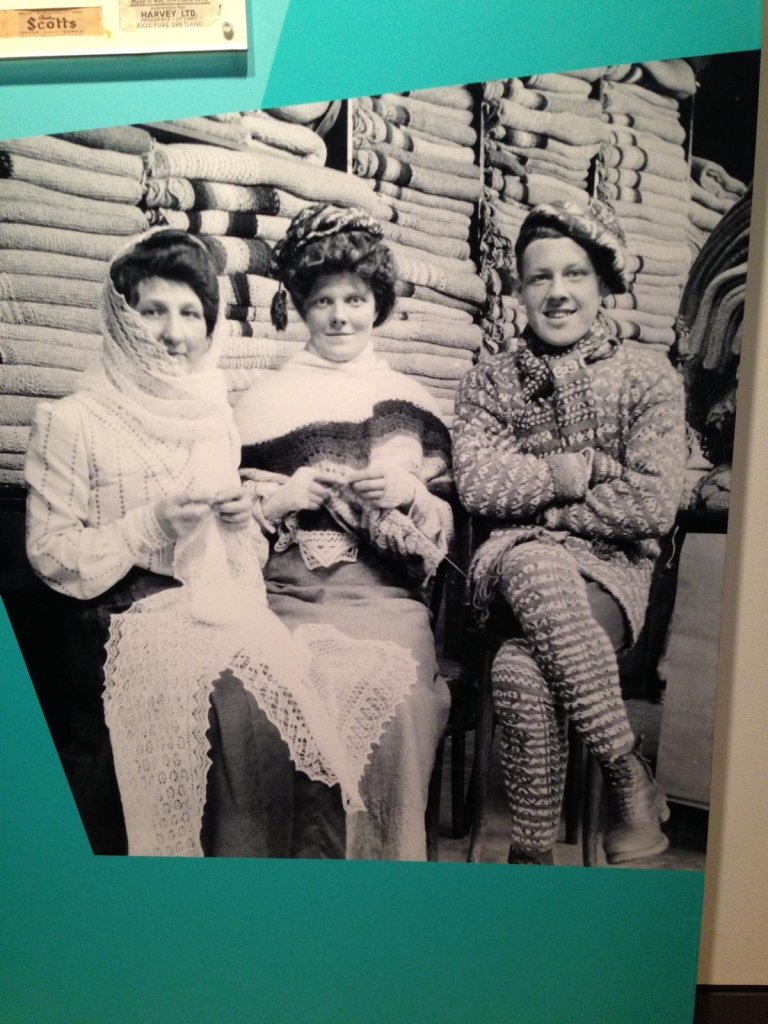

Tuesday was my final day in Lerwick and I returned to the Textile Museum which was originally the Shetland Textile Working Museum established by the Guild of Spinners, Weavers and Dyers. It was Bess Jamieson of Pointataing, Walls, who first collected historic Shetland textiles and commissioned faithfully produced replicas of certain styles and garments, caring and preserving them. I particularly wanted to see @maverick_knitter, Helen Robertson’s piece, Life Boy, as I knew I would be ‘meeting’ her later.

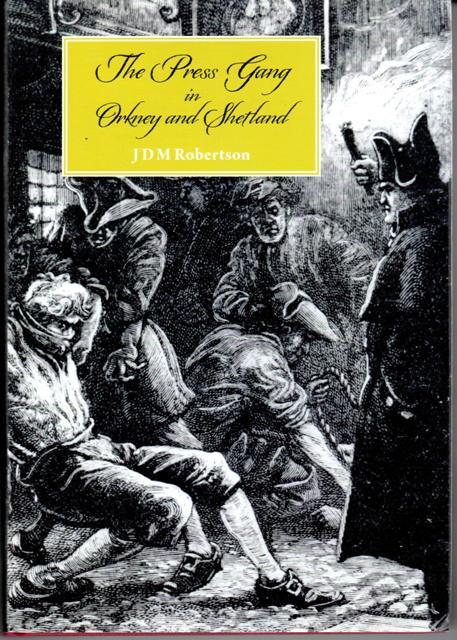

The following day, when Robertson and I walked and talked together, she told me that the project was inspired by the Press Gangs who, from 1800, took men forcibly away to sea. This left the women to manage family and land without them. Sometimes, they were unable to say goodbye, did not know where they would be going, and understood that the chances of death by disease were higher in the navy than when they were home.

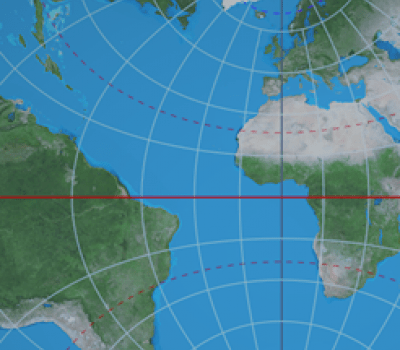

Impressment was the enforced seizure by government of men to work in the army or navy which was carried out by press gangs who were paid to bring in men. It was detested by everyone and was popularly considered to be an unjust system.

From an article by Kim Burns (as part of her dissertation), University of the Highlands and Islands

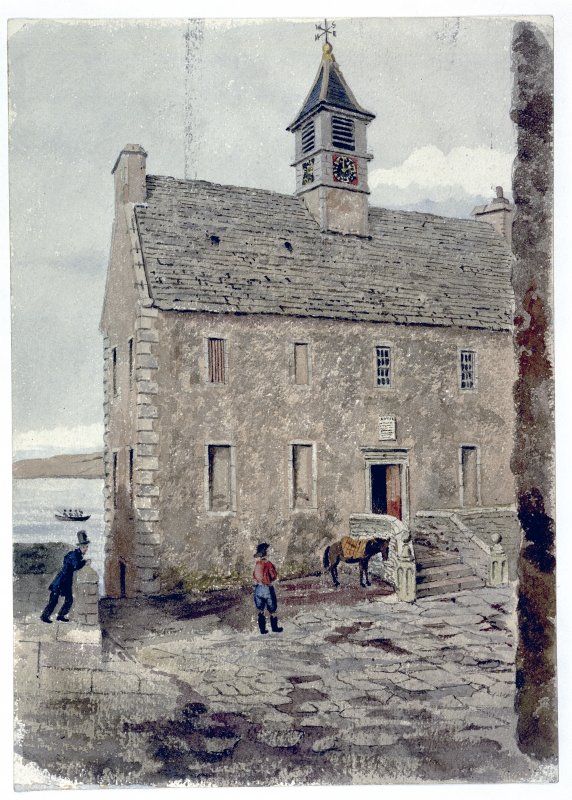

Earlier that morning, I passed by the 18th century Old Tolbooth (32 Commerical Street) which used to be where they locked the men up while they were waiting for the boats to come. Although Robertson didn’t consciously remember it, this building, which was the head quarters for the Red Cross when she was young, is now the Royal National Lifeboats Institute station and she later discovered that she had a photo of it in a research book with a life belt hanging outside!

From deconstructed sails I made big pieces of yarn and knitted a life belt. I did short rows in the round – a big piece of work, the size of a proper life belt. With Shetland oo (wool) and an old handline (a rope used for fishing without a rod), I knitted an infinity knot. It was the time that the European migrants were coming and there were lifebelts washing up. For me, it was all about the imbalance of power, the life and death thing, still touching wis every day.

Helen Robertson, from our chat

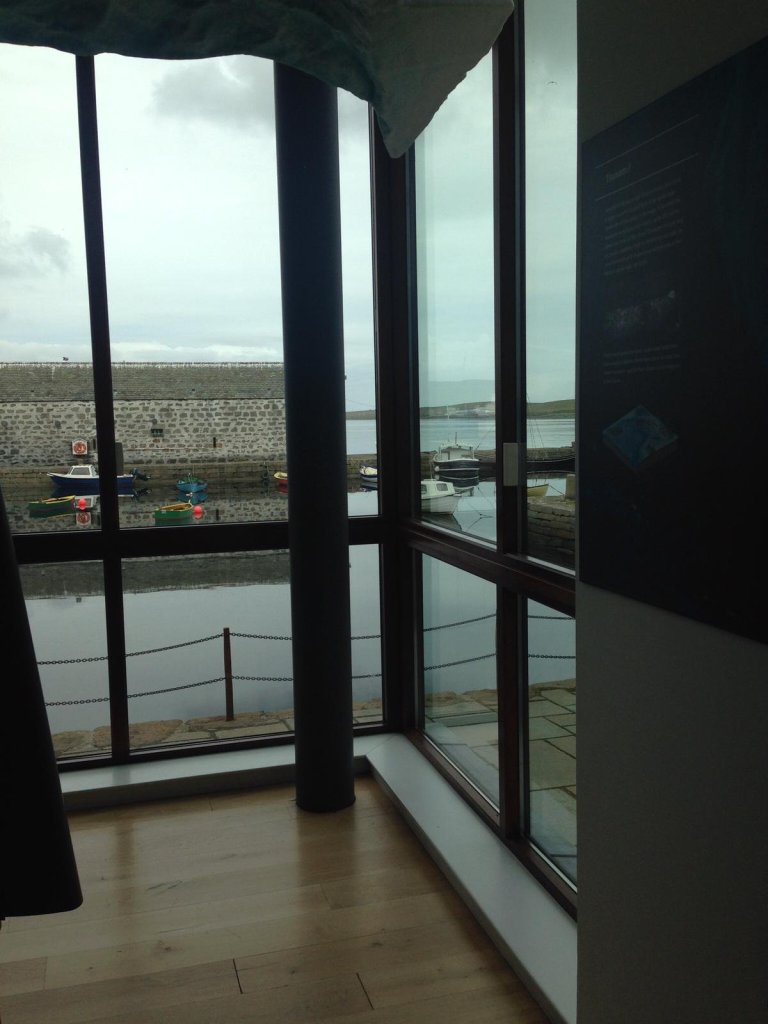

The Old Tolbooth is seconds away from the Esplanade and the harbour (where the Seabird Tour boats around Noss leave). The Jo Chapman sculpture Da Lightsome Buoy (2016) is nearby. Commissioned by the Pelagic Sculpture Partnership comprising of Shetland Catch, Shetland Fish Producers’ Organisation, Lerwick Port Authority and LHD in association with Shetland Arts, it celebrates Shetland’s long association with the pelagic (midwater trawls that have a cone-shaped body and a closed ‘cod-end’ that hold their catch) fishing industry.

The design ideas were influenced by a series of workshops, meetings, events, and the sharing of stories, photos and memories by the many people Jo met during her stay here.

Lerwick Port Authority

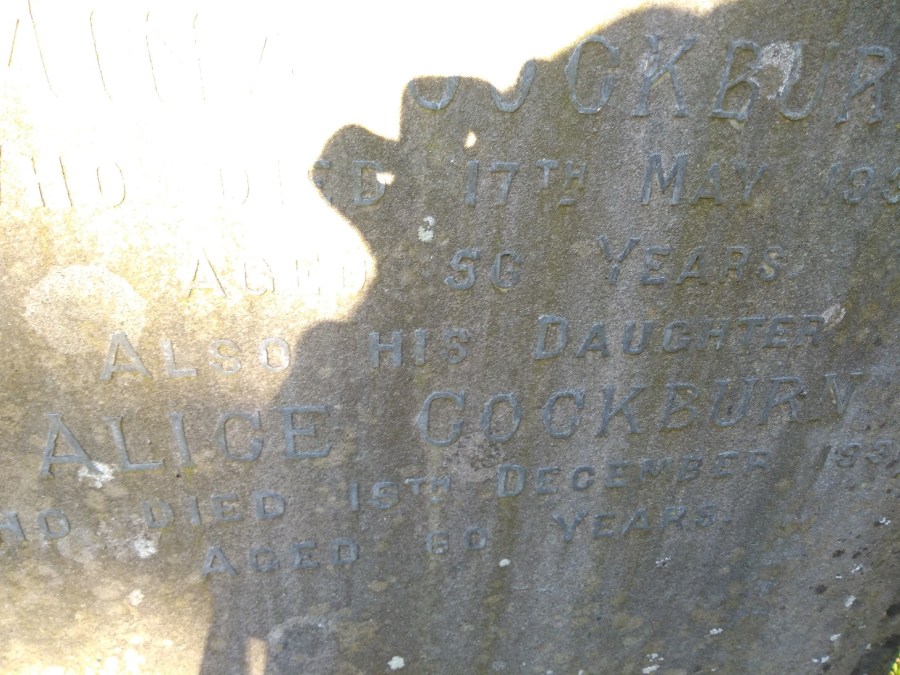

Heavy and solid-looking with a hole at one end, it is made of cast bronze and so has that dusky-turquoise look. The illustrations are of the female fish gutters and the fishermen (two gender divided groups), the historical and the new ways of processing the herring, and there are quotes and poetry in the local dialect from residents. It honours those who have died and who still labour in the industry today. The women who gutted the fish would sail around the British Isles and gut the fish in harbours such as Lowestoft and Edinburgh’s Newhaven. It was hard, mucky work and their hands were raw from the cold and the waters. There is more information on my blog about the herring gutters and the songs they sang.

The Böd at Gremista, where the Textile Museum is located, is at the edge of the town. I imagined myself walking on from there, northwards, via the Point of Scatland and Green Head.

The sewage works are close, so it wasn’t always a sweetly scented wander, but the seals on the rocks at Scottie Holm and the Rova Head lighthouse (UK Lighthose tour blog here) on Easter Rova Head made up for it, their sad-looking eyes and cats-whiskers so at odds with their on-land bulk. I watched them slip-slide into the sea and glide away so smoothly into the Bressay Sound, raising their heads like little periscopes to see what was going on back at shore.

The next day I was set to visit Northmavine (say Nortmayven with an emphasis on the ‘Nor’ and ‘ay’) in the north west where Helen Robertson lives with her family on a croft on the west coast of Sullom Voe (small bay or creek). 45 minutes by road, I took the number 21 bus to Brae. It’s a scenic route which skirts the Hill of Skurron (143m), travels along the Loch of Voe and through the town of the same name, where there used to be a whaling station operated by the Norwegian Whaling Company from 1904 until 1924. Then it branches by the side of the Olna Firth to Brae. Brae means slope or brow of a hill, and is just over an hour and half’s walk (according to google maps) to Sullom.

Near Sullom is a ruined house where Robertson placed her fine silver lace curtain. It was part of her Hentilagets Project. The name of the project comes from the scraps of oo (or fleece) from sheep’s necks and backs that would snag on dykes and fences. In the past, these were gathered and spun to make beautiful lace garments. We walked and then sat on a grassy knoll, a girsie broo, and looked at the windmill while she told me about her work.

a uniquely thoughtful aesthetic which celebrates, commemorates and reflects upon Shetland’s history and heritage

Kate Davies on Helen Robertson

Chef James Martin visits Helen Robertson’s brother at his Transitions Turriefield in Sandness which grows healthy, fresh, chemical-free fruit and veg to supply the Isles.

Helen Robertson is on instagram @helenrobertsondesign Her website is here.

Please note that my visit is a virtual one because I was unable to go due to the Coronavirus lockdown. I cannot, therefore, vouch for any of the trips which I have mentioned above or linked to.

Sullom a filmpoem by Roseanne Watt with music by Eamonn Watt